I am back with this series of do’s and don’ts of sourdough starters to help you understand the science behind them so you can make more informed decisions in a time where everyone seems to have “the ultimate recipe and process” for sourdough. Spoiler alert: sourdough is not a one-fits-all kind of thing. This week’s topic is: feeding ratios.

Last time we talked about the age of our sourdough starter and why claims that a starter not working because it was too young were probably wrong, and the issues had more to do with how often the sourdough starter was being fed.

After learning how often we should feed our starter, the next question is “How much should I be feeding my starter?” So let’s dive into Feeding Ratios!

Buy this mango kiln wooden tray on BE HOME

What is a feeding ratio?

Feeding ratio refers to the proportions of sourdough starter, water, and flour we use to refresh our starters. Typically, everything is based on the amount of starter. I’m sure you’ve seen 1:1:1 ratios, or 1:2:2, or 1:10:10… It’s usually given as starter:water:flour, so a 1:1:1 ratio means 1 part starter, 1 part water, and 1 part flour. 1:2:2 means 1 part starter, 2 parts water, and 2 parts flour, and so on.

What happens if I change the feeding ratio?

Nothing, just that your starter will peak at different times. You can adjust feeding ratios to your needs and to whatever your starter needs. In the first post of this series, we talked about how a 1:1:1 ratio might be more convenient if you’ve been feeding your starter too often. But maybe your kitchen temperature and overall conditions allow you to keep a starter at room temperature and feed it at a 1:1:1 ratio once or twice a day. Or maybe you live in a very warm and humid area, where a 1:1:1 ratio is too limited and the starter peaks too fast. If that’s the case, you will probably benefit from a 1:10:10 ratio.

If you like to keep your starter in the fridge, maybe you prefer to refresh it a few times before baking and, in this case, you can use the standard 1:2:2 ratio. Maybe you prefer a “no discard approach” and just take a little bit of starter from your jar and feed it at a 1:10:10 or 1:15:15 ratio to end up with the exact amount of starter you will use on your recipe.

Ideal feeding ratios

The ideal feeding ratio is the ratio that works for your schedule and/or needs is the ideal ratio for you. And this ratio can change at any time. Sourdough is alive, but we have a certain control over how fast or slow we want it to grow.

For a given temperature

The smaller the ratio, the faster it’ll grow because the amount of food for the bacteria is more limited. A larger ratio will result in a starter that will take its sweet time to peak.

Example 1: You have a few slow hours in the middle of the day and it’s the only moment you can prepare your dough. Then feed your starter a 1:1:1 ratio early in the morning and it’ll be ready around the time you’re free.

Example 2: You are having an extremely busy week. You can only prepare your dough tomorrow sometime during the morning but you only have time for your starter today. Then maybe a 1:10:10 feed today in the afternoon will work.

For a given feeding ratio

The higher the temperature the faster your starter will peak. And the lower the temperature, the longer it’ll take to peak.

Example 1: It’s winter and your kitchen is usually at around 66-68F (19-20C), you can feed your starter a 1:2:2 ratio on Friday evening and it’ll be ready in the morning. You can start preparing your dough on Saturday morning.

Example 2: You live in a very hot and humid place. Maybe higher feeding ratios (plus using fridge cold water) is what works for you. Feed your starter in the evening at a 1:15:15 ratio and it’ll be ready the next morning, or feed your starter at a lower ratio in the morning, and you can probably start your dough early in the afternoon.

All these are examples, of course, you know your starter better than anyone and can probably anticipate how it’s going to behave. But what if you are new to sourdough? Then let’s experiment a bit!

How to get familiar with your sourdough starter

If you don’t know your starter very well, you need to record its behavior for a little while. For that follow these simple steps:

- Kitchen temperature: Record your kitchen temperature, I usually just follow my house thermostat, but you can use any thermometer.

- Feeding ratios: Based on your temperature choose a feeding ratio. Unless you live in extreme cold or heat conditions, I would go for a 1:2:2.

- Time to peak: Record the time of the feeding and keep an eye on your starter until it peaks, then record that time and calculate how long it took.

Anything from 8-12h cycles using a 1:2:2 ratio falls under normal behavior for my starter. During winter it grows slower, during summer it grows faster. My house has AC, in winter we keep it from 66-69F (19-20C), and during summer we keep it 70-74F (21-23C), but when we are not home we let the temperature increase a bit, so during North Carolina’s hot summer days, I sometimes use 1:10:10 feeding ratios.

Can I adjust the water?

A typical liquid sourdough starter is a 100% hydration dough. But sometimes it’s interesting to play with the hydration levels of our starters. For example, if you’re working with Lievito Madre, you know it is a starter at 40% hydration (ish). Dryer starters tend to be a bit sweeter and less acidic and they’re fabulous for sweet breads. But they do take a bit of extra elbow grease to maintain. On the other hand, liquid starters at 100% hydration are very easy to maintain. But can you use 85% hydration? or 125%? of course! You’ll have to calculate how much water you need.

How do I calculate the water for feeding ratios?

If you want to experiment with other water contents in your starter, you need to know just a basic concept. If you want LESS water than flour, you will have to multiply the flour content by 0. something and if you want MORE water than flour you will have to multiply by 1.something

Example 1

If you want a starter at 75% hydration, then you decide the ratio of starter and flour, calculate the flour, and finally, multiply that amount by 0.75

Let’s start with a 1:3 ratio of starter:flour and 10 g of starter. This means we have 30 g of flour (3 times the amount of starter). To calculate the water we multiply the flour by 0.75:

30 x 0.75 = 22.5g of water

Example 2

If you want a starter at 125% hydration, then you decide the ratio of starter and flour, calculate the flour, and finally, multiply that amount by 1.25

Let’s start with a 1:5 ratio of starter:flour and 15g of starter. This means we have 75 g of flour (5 times 15g). To calculate the water we multiply the flour by 1.25:

75 x 1.25 = 93.75g of water

(you can round it up to 94 or 95 and it will be fine)

Can I use volume instead of weight for feeding ratios?

Working with weights allows you to be more precise and it makes the process easier to repeat. Weights are much more accurate to measure than volume. At least with regular home equipment. If you’re new to sourdough, bread baking, or baking in general, I would strongly suggest you use weight instead of volume. This way you’re already avoiding possible differences between feedings that could potentially lead to different outcomes. You will have a better picture without doubting if the differences you see come from off feeding ratios or something else. If you want an affordable scale I use THIS ONE, I’ve used it for many years and I think I’ve changed the battery once. Baking doesn’t need to be expensive!

With this being said, you do what works for you, if you are comfortable using volume measurements, use them. Just try to be as precise as possible (Can you tell I’m a scientist? 😉 )

How do feeding ratios work with other flours?

As far as bacteria go, the same! However, different flours make different doughs so you might not see your starter peak as a wheat starter would. You will have to find how the peak looks for different flours. Also, some flours absorb a lot more water than others, and a 100% hydration starter might look very different depending on the flour.

All this might seem a bit complicated but I assure you that once you start, you’ll understand right away and you will start to understand your starter much better!

One last thing about sourdough starters

You don’t have to put yourself in a box and follow exactly what others are doing. Use the feeding ratio that works for you, the hydration that works for you, and the measurements that work for you (volume vs weight). The idea of this series of posts is to give you enough information so you can make an informed decision that will work for your particular needs. Don’t be afraid of experimenting!

Here are a few recipes that you can try if you’re starting in the art of sourdough!

Sourdough burger buns (cookout time is here!)

Sourdough marble rye bread (one of the blog favorites!)

Sourdough Challah (another favorite!)

Happy Baking!

Sourdough starter troubleshooting – Feedings

Lately, I’ve seen people saying things like “a 4-week-old sourdough starter is too young” to justify someone’s problems with their bread or starters. This statement is just wrong and very discouraging for new bakers, or people on a budget who can’t just throw flour every day for feedings.

Two weeks (as a rule of thumb) should suffice to have an active and powerful starter. Let alone 4 weeks!. In fact, depending on the method you used to create your starter, you might be able to make bread in just a week!

Chances are that the age of your sourdough starter has nothing to do with the problems you might be having. In this series of posts I’m going to delve into the science of your starter so you can troubleshoot whenever you need. Although, I hope you only need to troubleshoot it once!

WHAT DEFINES THE STRENGTH OF YOUR SOURDOUGH STARTER?

It’s not time, it’s THE NUMBER OF ACTIVE BACTERIA present in your starter. If your sourdough starter is not ready after 2 weeks (and depending on the method, maybe just a week), your feeding schedule probably needs adjustment. Either you’re following a fixed schedule instead of refreshing the starter when is ready, or you’re using the wrong ratio and not introducing enough nourishment for all the microorganisms to reproduce. Let’s dive into it:

BASICS OF SOURDOUGH BACTERIA

Bacteria in sourdough follow a 4-phase growth curve: Lag phase, exponential phase, stationary phase, and death phase, (For more of this go check this post where I tell you all about it). During the lag phase, they’re not multiplying yet; they’re just checking the environment and synthesizing the proteins and products they need to start multiplying (growing). At this stage, whichever ratio you used to feed your sourdough starter introduced some nutrients for the bacteria.

The second phase involves the exponential growth we’re all familiar with; the duration of the second phase(how much the starter is going to grow) purely depends on how much food there is available for the bacteria. Or better said, how many grams of food per bacteria were introduced. Let me explain:

Imagine a family of 4 people that has 4 cupcakes; they get one cupcake per person, they will run out of cupcakes fast, and they are not going to get a lot of weight because they only ate one cupcake each. Now let’s say we have the same family, and instead of 4, we have 12 cupcakes; then they get 3 cupcakes per person, it’s going to take longer to finish them all, and they will gain more weight because there was more food, right?

Same with your sourdough starter! Smaller ratios mean that the food is going to run out faster, and the growth (bacteria multiplying) is going to take place for a shorter period of time. Now let’s say you used a 1:3:3 ratio (like the family), the bacteria have a lot more food, so they’ll be eating for longer; therefore, it’ll take a longer time to finish all food.

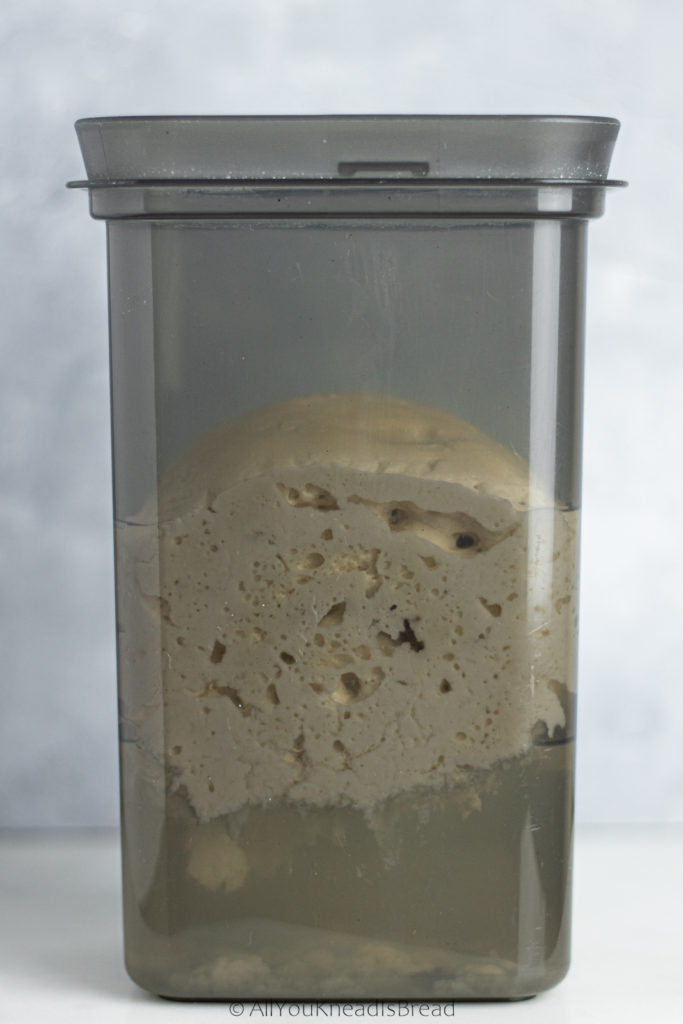

What happens after the bacteria eats all the food? Bacteria multiply as long as they have food (energy), once all the food is depleted, they can stay active for a while, this is what we call the “peak” (the stationary phase), and the reason we say this is the best moment to use your sourdough starter is that it’s when there’s the largest number ALIVE AND ACTIVE bacteria.

After the peak, bacteria start going dormant; some die too (death phase). When using a 100% hydration starter (Keep in mind that gluten-free flours behave a bit differently because of the lack of gluten), this moment usually occurs at the same time the gluten network starts breaking down. That’s when we see the starter collapsing (there are more variables involved in this, but for now, let’s imagine the kitchen is at around 20C, not too cold, not too warm, so neither the bacteria growth nor the gluten in the starter is compromised because of the temperature).

WHY IS MY SOURDOUGH STARTER NOT DOUBLING?

One of the main problems I see is that people refresh their sourdough starters based on time (fixed schedule) and not when it’s ready. So when you take part of your starter out too early and introduce new flour and water, what you’re really doing is reducing the number of active bacteria before they have a chance to multiply. What you’re doing is bringing more cupcakes to the family but taking away a few members, so yes, there are lots of cupcakes, but not enough people to eat them in a reasonable time. And the more you do this, the more you feed your starter too early, the more bacteria you’re taking away, and the more you’re reducing the fermentative power of your starter by introducing unfermented flour. It might get to a point where the number of bacteria is so low that you might not see any growth in maybe 12 hours! (Even though they’re still working hard multiplying!)

Basically, you are keeping your sourdough starter in a continuous lag phase or a very early exponential phase.

HOW CAN I FIX MY SOURDOUGH STARTER?

Easy, just WAIT!, leave the starter at room temperature for a whole day; it’s not going to grow mold, and it’s not going to go bad (if it does, then your starter was already contaminated with other microorganisms). If the problem is a very low number of bacteria, they need time to get out of the lag phase and get well into the exponential phase. Wait, and most likely, you’ll see some growth, maybe in the form of small bubbles, maybe you can smell it, or maybe you can even see the dough growing a tiny bit.

If you don’t keep a large amount of starter (less than 40 g total), you can add more flour and water without discarding anything and wait for it to grow again; then you can start with regular feedings. If you keep a larger amount, you can discard some and refresh it. At this stage, since the problem was (most likely) the low number of bacteria, you don’t want to give it too much food all at once because that might take too long to ferment, and you’re going to get frustrated. I would aim for a 1:1:1 ratio for a couple of feeds until you see obvious signs of activity and the starter growing. Then wait for it to peak, and decide which ratio works better for your situation.

Wrapping up

Feeding ratios are another big thing when it comes to sourdough starters, in part II I’ll tackle feeding ratios and some outrageous advice I’ve seen people tell newbies. Things like “if your starter doesn’t double in 4 hours then it’s not powerful enough”. If you’ve heard that before, stay tuned! And if you have questions write them in the comments so I can try to respond as best as I can.

You can find me on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest, and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

Happy baking!

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.

Whey bread: my new favorite

How on earth did you come up with a whey bread recipe? I’m glad you ask! A few months ago I started to make my own yogurt. But with homemade yogurt came leftover whey. I don’t like throwing away things that I can use, especially something that 1) I know it’s an industry waste very difficult to deal with and 2) is not milk but smells like it and therefore could give great aroma to my bakes. I thought I could find a good use for it, and the most obvious one for me was to try my hand at a whey bread. Spoiler alert: it’s AMAZING!

For this recipe, I decided to use active dry yeast (you can also use instant if that’s what you have). I know I know… I’ve been on a sourdough roll for quite a while but because I wasn’t sure if making a 100% whey bread was possible, I wanted to try first using yeast. Then, during the recipe development, I realized that I needed to reconnect with my beloved yeast. The challenge of making something with sourdough is exciting but yeasted bread is delicious too and more convenient when you don’t have the time or patience for sourdough. And honestly, I think this recipe is perfect the “whey” it is *pun intended* 😉

Check the notes in the recipe box for the baker’s percentage, the measurements are for a large loaf pan.

What is whey?

For those who don’t know what whey is, it’s a by-product of the yogurt-making process. Once the milk is curdled and the yogurt is set, the yogurt is strained to get a creamier texture or Greek-style yogurt. The leftover liquid is known as whey or yogurt whey. It’s yellowish and it can be clear or a bit cloudy, it has a milky smell and it’s acidic. If you want to know more about the composition check this scientific article.

This whey is not the same whey protein powder has, they’re called the same, but they’re different. Protein whey is also known as “sweet whey”.

When I make yogurt I make 2 liters at a time; There’s a lot of whey in 2 liters of yogurt! I didn’t want to throw it away before I at least tried to do something with it. I also know whey is a huge problem in the dairy industry. It’s a by-product that pretty much goes to waste and it really poses an environmental problem. You can’t just throw it away because it has a lot of microorganisms and nutrients for other microorganisms that can lead to algae growth. The low pH can acidify the surroundings and thus affect the ecosystem where it’s dumped. It’s a big no-no.

Making the most of whey waste

Many researchers are looking into possible uses for whey in an attempt to relieve the industry from this problem and to minimize environmentally dangerous practices. Believe it or not, the Greek yogurt industry creates billions (billions with a b!!) of liters of whey. This article explains it very well, it’s an interesting read if you’d like to know more about this issue.

But we, bakers of the world, home cooks, kitchen creatives, zero waste enthusiasts… always find a use for everything! So, to your question “Can you make bread with whey?” The answer is YES, YOU CAN! And whey bread is actually now one of my favorite things to bake!

Using whey in bread

For this recipe, whey is the only liquid I use. Even for the yudane (which we’ll cover later). If your whey is clear or cloudy is not going to affect the bread. I’ve tried with both and they work the same.

I was a bit worried at the beginning because I wasn’t sure if the lower pH would affect gluten development or the final texture. But good news! The dough behaved beautifully! It’s very aromatic and you’re going to fall in love with this whey bread! And you can even keep the whey in the fridge for a couple of weeks before you use it. Its low pH and good microorganisms can extend its shelf life for quite some time!

About this whey bread recipe

Let’s get into the tidbits of the recipe! After testing different ingredient ratios, I decided to introduce some precooked flour. Some of you might have heard about tangzhong and yudane methods. Both are based on the same idea: the gelatinization of starch. Tangzhong is a roux and it’s made with a 1:5 flour to water ratio. Yudane, however, is a 1:1 flour to water ratio, and instead of gradually increasing the temperature and cook the mixture, you boil the liquid and pour it on top of the flour.

I’ve worked with both methods and I love them both. The gelatinized starch in the precooked flour makes quite a difference in the texture of the bread. I always mention how important gluten development is, but gluten development doesn’t only mean building the gluten network. It means incorporating all the necessary elements into the network. And that includes starch granules that will gelatinize during baking. These gelatinized starch granules give the crumb some springiness and elasticity, which are key for soft and fluffy bread.

How to make the yudane for this whey bread

If you have a stand mixer or some machine to knead the dough, I’d recommend you prepare the yudane with it. Measure the flour and keep it in the bowl. Boil a bit more whey than the amount you’ll need because some of it will evaporate. When it comes to a boil turn on your stand mixer, quickly measure the weight of the whey you need in another container, and pour it into the stand mixer bowl and knead it until you can touch it without burning yourself.

If you do it by hand, also measure the flour and keep it in the bowl, proceed to heat the whey in the same manner, and when it comes to a boil measure the amount you need directly on the bowl where you have your flour. Place the bowl on the scale, add the whey, and quickly, with a spatula or a wooden spoon mix the dough well and knead it until you have a sticky dough ball.

If you can, use a heavy bowl, so it doesn’t move around while you’re stirring and pouring the boiling water.

The yudane method explained

Usually, people make the yudane the night before baking and let it cool down in the fridge. However, I think that approach is not the best if we want to maximize the possibilities of adding gelatinized starch to our dough. Why? Because of something called starch retrogradation.

Starch is made of two monomeric units: amylose and amylopectin. At room temperature, these two compounds have a crystalline structure (not that they’re crystals per se, but their atoms are arranged in the space as crystals). In presence of heat and water, the starch granules swell and burst. When this happens, the crystalline structures of amylose and amylopectin are lost, the chains can interact with even more water, and the mixture becomes a gel, thus the “gelatinization” part.

However, the gelatinization process is not 100% irreversible. The moment heat is no longer applied and the temperature of the gel starts going down, some of the monomers start re-crystalizing. That means that as they go back to their original structure, they start losing the gel properties and become solid again. This process is called retrogradation.

Starch retrogradation is quite a big deal in starch science and it does have a role in bread staling. It’s also one of the main reasons bread gets hard and crumbly when we put it in the fridge.

Why I don’t put my yudane in the fridge

The retrogradation process is accelerated at cold temperatures. That’s why sauces or custards that have flour or starch harden in the fridge. If we put the yudane in the fridge, the starch retrogradation will go faster than if we just leave it at room temperature. We can keep more gelatinized starch and our bakes will be even better if there’s no cold involved.

Keep in mind that even if we let the cold yudane come back to room temperature, the retrograded starch won’t gelatinize again. Gelatinization starts at high temperatures (>65C/150F)

This is my personal preference when making yudane. I find it’s also more convenient because I always forget to prepare things the day before. But obviously, you can leave it in the fridge if that’s what you prefer.

When your yudane is ready and it’s not too hot, you can either start right away, or you can wrap it in plastic until you start making this whey bread.

How to ferment this dough

Since this is a yeasted dough, it’s going to be a 1-day bread. And in just a few hours you should be able to enjoy a nice slice of this whey bread that’s going to enamor you!

The bulk fermentation will take about 2-3h, proofing will take a bit less. These are just a guide, the total fermentation time depends on how hot your kitchen is, etc etc. Proofing is where things can be different depending on what type of loaf pan you have.

Proofing on a Pullman loaf pan with lid

I have this Pullman loaf pan with a lid. I must say… it’s large. I underestimated the size when I bought it some years ago. At the time I was baking just for myself. But now this size is very convenient because it makes a loaf large enough to last the whole work week and feed 2 people. I’m talking breakfast toasts, lunch sandwiches, mid-afternoon snacks…

Make sure you oil the pan and the lid. After you shape the dough, let it ferment until the dough is 1cm from the top. Then put it in the oven. If you bake the loaf when the dough is already touching the lid and is filling almost all the pan, the dough won’t have enough space and might pop the lid. As the bread keeps rising the first few baking minutes it might push the lid and you might hear a little explosion. Nothing major, but if you’re not expecting that it might scare you. I know because I almost had a heart attack when I heard that myself!

If this happens though, carefully put the dough back in the tin with the lid and everything (it will deflate after the shock) and continue baking. The worst that can happen is that the loaf will have a wonky shape. It might even be a bit smaller than you wanted. But it’ll be totally edible.

Proofing on a loaf pan without a lid

In this case, there isn’t any risk of “explosion”, but there’s a risk of mushroom shape loaf. If this happens it’s possible the bread gets stuck in the edges of the pan and it will not come out of the tin after it cools down. The best you can do is control the proofing and start baking when the center of the loaf is, at most, 1-1.5cm above the edge of the pan. This dough is very elastic, so it’ll have a nice oven spring. For smaller loaves, I use this loaf pan and it serves me well. It’s very versatile and useful for small cakes, banana bread, etc.

How to shape this whey bread

Deflate the dough gently and well by kneading it for a couple of minutes, let it rest for 5 minutes, and then roll it into a rectangle slightly narrower than the length of your loaf pan and as long as your dough allows you while keeping at least ½ inch thickness (if it’s thinner it might get stuck on your counter and be easier to trap air as you roll it). Shape the dough into a log and put it in the pan. If you’re using a Pullman loaf, close the lid. If your loaf pan doesn’t have a lid, cover the dough with plastic wrap or put the pan inside a large enough plastic bag.

How to bake this sandwich whey bread

Whey has significant levels of galactose, a monosaccharide that’s also considered a reducing sugar. These types of sugars are the ones responsible for Maillard reactions. To the already happening Maillard reactions in bread, we’re adding more reducing sugars, thus your loaf will brown faster than usual. This will make a bit more difficult to test the doneness because the color can be misleading. You take the bread out of the oven when it’s still not fully baked, yet the outside is pretty dark.

For this, it’s better to test the temperature in the middle of the loaf. Once the temperature hits 96C, the bread is done! I have this thermometer and I am very happy, it’s fast and you can also put the probe at an angle, so you don’t burn yourself with the top side of the oven.

Baking with a lid

Here you have two options: you can bake the bread half the time with the lid on. When it starts browning remove the lid and continue baking until it’s done (by testing the inside temperature). Or you can bake with the lid on until it’s fully baked. If you remove the lid halfway, the loaf can get a slightly domed shape that will disappear after it cools down. However, there’s some risk for getting a weirdly shaped loaf. On the other hand, if you bake with a lid, the top might get a concave shape after it cools down.

This all pure aesthetics, it’s not a big deal and it’s not going to affect the flavor or fluffiness of the bread. But sometimes we just want that perfect square toast. I find it easier to bake with the lid at all times, and then I have my process to cool this whey bread down to keep the square shape.

Baking without a lid

If you don’t have the Pullman-style loaf pan, your bread will have a lovely round top and you won’t have to worry about losing the shape while it cools down.

How to cool down your whey bread

One little issue that I’ve encountered when making Pullman loaves is the concave shape the loaf gets after it cools down. It’s a bit hard to find the exact moment to take the Pullman loaf pan lid off. If you take it off too early, the loaf might have a convex shape (like a mountain), but if you take it out too late, it’ll have a concave shape (like a valley).

My strategy is to bake the bread with the lid on at all times and I cool it down upside down for the first 30 mins. First 10mins in the tin, and the rest 20 out of the tin (otherwise the steam will condense on the bread and leave it wet and soggy). If you’re up for the challenge, you can keep turning the loaf upside down every 20 minutes until it’s room temperature. It worked for me, but that’s not something I’ll do all the time. Mostly because I forget about the loaf after it’s baked 🙂

How to store this whey bread

The yudane helps a lot keeping this whey bread fluffy for a longer time. I’ve tested this recipe with and without yudane and there’s a big difference (it stays fluffier with yudane). I’ve kept this whey bread at room temperature as is (not in a bag) for 5 days, just keeping the open side on the plate so it doesn’t get extremely dry. The crumb did dry out over time, but the bread was totally edible and after putting a couple of slices on the toaster it was perfect. The fats (from butter and eggs) kind of seal the crust of this bread, keeping the moisture inside. So while the crust might dry, the crumb remains nice and soft.

Now, this was an experiment, I don’t recommend leaving the loaf as is on the kitchen counter. If you have a square plastic container, you can slice the loaf up and place the slices there. You can also keep it in a ziplock bag and slice it as you need. You can cut the slices and freeze them and then just pop them in the toaster for 1 or 2 cycles when you want a slice.

If you make homemade yogurt I encourage you to try adding whey to your loaves, especially enriched ones! I am stunned by its versatility and incredibly milky aroma! I’d go as far as to say that if you use whey, you might even be able to skip powdered milk in some recipes!

Frequently asked questions

If you follow me on Instagram you might have seen me playing around with this bread. And I received several questions while I was developing this recipe. I hope they can be useful for you too!

Can I use whole wheat flour to make this whey loaf?

Yes, you can, always keeping in mind that cereal bran will alter the dough a little. The more bran, the more liquid you will need and the less smooth your bread will be. I have this recipe for a whole wheat loaf that you might like to try using whey.

Can I use gluten-free flour?

I get this question quite often, and the answer is no. A gluten-free bread requires a lot more testing and different ingredients to make sure you can mimic the properties of the gluten proteins. So you can’t just substitute one flour for the other. If you have experience with gluten-free bread, then you can probably twitch some of your recipes to add whey.

Can I make my whey bread in a Dutch oven?

I haven’t tried it, but I don’t see why not. As long as you control the temperature and you don’t mind the shape of the bread. Still, keep an eye on the dough, because it’s possible it’ll rise more in the oven than a lean dough would, you don’t want to get the dough stuck in your dutch oven.

Can I use parchment paper in the loaf pan?

I don’t see why not! my Pullman loaf pan doesn’t need it, even if I don’t spray oil. But if you’ve had problems before, parchment paper won’t affect your bread.

Can I use oil instead of butter?

If we were talking about other recipes I might not recommend you to do so. Butter and oil behave differently and can lead to very different results. Even solid and melted butter behave differently (You can read about that in this brioche with sourdough discards recipe).

But for this recipe, butter is not the key ingredient so you can substitute it for oil. I have tried using olive oil and it also makes delicious bread!

Whey bread: Your new favorite loaf

This sandwich whey bread is super flavorful, soft, and perfect for sandwiches and toasts. It's also a great way to use your leftover whey!

Ingredients

Yudane

- 130 g bread flour **Check notes for the baker's % to scale down this recipe to a smaller loaf pan**

- 130 g boiling whey

Whey bread dough

- 260 g yudane

- 520 g bread flour

- 150-190 g whey * See notes

- 10 g active dry yeast

- 2 eggs

- 90 g sugar

- 12 g salt

- 80 g softened butter

Instructions

Yudane

-

Add 130g of bread flour to your bowl.

-

Heat a bit over 130g of whey and when it comes to a boil weigh 130g and quickly add it to the flour.

-

With a wooden spoon or with a stand mixer mix the flour and whey until it forms a sticky dough. If you're not ready to bake wrap it in plastic and keep it at room temperature until you're ready to start your bread.

Whey bread dough

-

Mix the room temperature whey, the yeast, and the eggs and let the mixture sit for 10 minutes.

-

Add the sugar to the egg mixture and give it a whisk.

-

In the bowl where you have your yudane add the egg mixture and break up the yudane a little bit.

-

Add flour and salt to the bowl where you have the yudane and the wet ingredients and mix everything until you don't have dry flour particles. Cover and let it sit for 20 minutes.

-

After 20 minutes start kneading, if the dough feels too stiff and you didn't add all the liquid whey, add a bit more. Once the dough starts coming together add the softened butter and continue kneading to incorporate it.

-

Knead until the dough becomes smooth and elastic. It shouldn't stick to your fingers and it should feel nice to the touch.

-

Place the dough in a lightly oiled container, cover it and let it ferment at room temperature for 2h or until it at least doubled in size.

-

deflate the dough gently and let it rest, covered, for 10 minutes.

-

Dust the dough and the counter lightly with some flour and with a rolling pin roll your dough into a rectangle slightly narrower than your loaf pan. Roll the dough into a log and place it in your oiled loaf pan.

-

Let the dough ferment a second time until it's 1-1.5 cm from the edges of the loaf pan (if baking with a lid), or until the dough is at most 2cm above the edges of the loaf pan (if baking without a lid). This should take about 1.5h at a room temperature of 74F/23C. Check the post for more detailed information about this.

-

Before the dough finishes fermenting preheat your oven at 350F/175C.

-

When the dough is ready bake at 350F/175C for 35-45minutes or until the inner center temperature reads at least 205F/96C (Time will depend on the oven).

-

Take the loaf out and let it cool down for 10 minutes in the pan before you remove it from it. If using a Pullman loaf pan cool it down with the lid on upside down for 10 minutes and another 20 minutes without the lid (Check the post for detailed information about the cooling process).

Recipe Notes

(For detailed instructions, explanations, and FAQ refer to the post)

* The amount of whey depends on how much your flour can absorb. My flour has 12.7% protein content and I can comfortably add 170-180g, with stronger flour (14% protein) I need 190g of whey.

**Baker’s Percentage:

Yudane Flour: 20%

Yudane Whey: 20%

Dough flour: 80%

Dough whey: 29.2%

Eggs: 15.4%

Sugar: 13.8%

Yeast: 1.5%

Salt: 1.8%

Butter: 12.3%

If you liked this recipe you might also like:

- This super easy kefir bread (video included!)

- This sourdough marble rye loaf, perfect for sandwiches

- These sourdough burger buns that don’t fall apart

- These delicious sourdough blueberry muffins

- These tasty brie sourdough buns

You can find me on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest, and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.

Happy Baking!

The science of your sourdough starter

Welcome to a new section of my blog: Bread Science Fridays! In this section I will be indulging on my nerd side and talk about the science of many things behind your beautiful bakes. This week’s post is dedicated to our beloved sourdough starters and the science behind them!

Ever since the pandemic started, more and more people jumped into sourdough. So, I thought it could be fun to explain scientifically what happens when you feed your starter (or build your levain).

A sourdough starter it’s just a culture of microorganisms that are alive and perform their own biological activity. These cultures are composed, mostly, by different strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), saccharomyces yeasts, and some candida yeasts among others.

In this post, you will learn the phases your starter goes through during a feeding cycle, why using your starter at its peak of activity is important, and the science behind it!

A couple of things about biology

In microbiology, a strain of a certain type of microorganism is like a subtype of named microorganism. For example, the lactic acid bacteria type would be the lactobacillus but there are many subtypes (Strains). Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Lactobacillus Sanfranciscensis, Lactobacillus Reuteri… They’re all LAB but with some differences (from shape to optimum living conditions).

Each strain has its specific optimum living conditions. That is the optimum temperature, water activity, pH… that will make the fermentation rate the fastest. The fact that a microorganism is “happy” at 28C, for example, doesn’t mean that it cannot perform its biological activities at 29C or at 20C. It means that the performance will not be the best. As you know, it slows down at cold temperatures. However, it’s higher temperature that pose a threat to the microorganisms. Too high temperatures will inhibit and eventually kill the bacteria.

The bacterial growth curve

Bacteria, as living organisms, grow, multiply, and die. The reason our sourdough starter is resilient is not because the bacteria are indestructible, its’ because there are millions of them and not all of them are the same age. They are in different growth phases. While maybe most of the bacteria are dying, some might have just been born.

Bacteria and yeast multiply by dividing themselves into two. 1 becomes 2, 2 become 4, 4 become 16, etc. This mechanism is called binary fission. Therefore, their growth is exponential. In microbiology, this growth is depicted using growth curves.

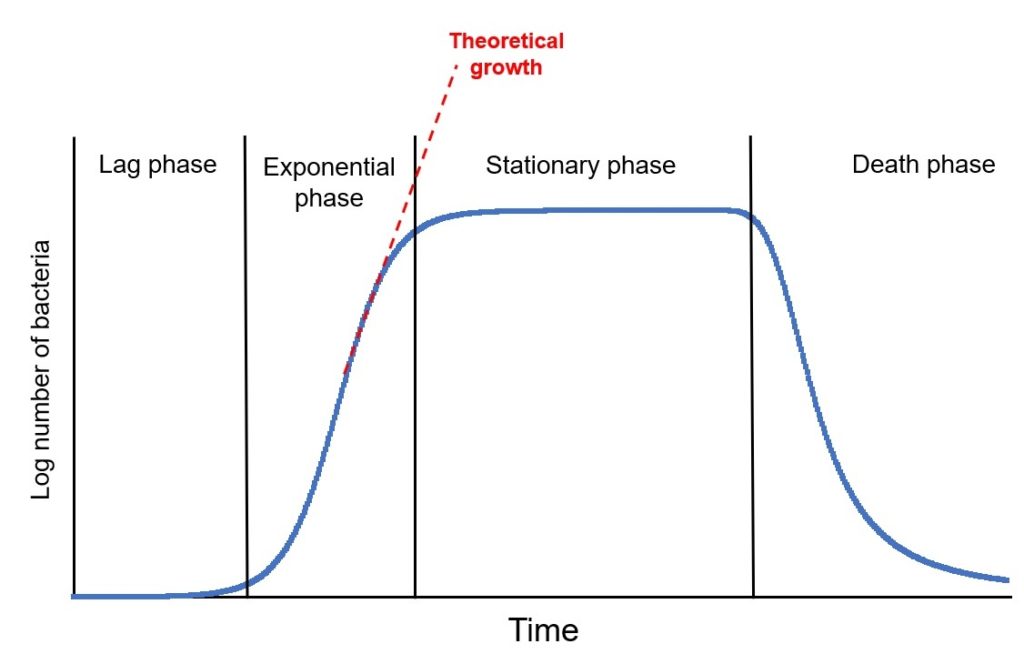

Bacterial growth curves are specific for each strain of bacteria in a specific set of conditions (Changing the temperature will change the curve). In these curves we can see the 4 phases bacteria undergo from the moment they’re born to the moment they die. A generic bacterial growth curve would look similar to this one:

Our starter will follow this growth cycle too. Understanding what happens in each phase will help us understand our starter and when we should use it for baking to prevent a excess of sourness

The phases explained

Phase 1: Lag phase. This is the very beginning of the curve. At this stage, the microorganisms have enough nutrients and are active but they’re still not multiplying. What they’re doing is synthesizing proteins and getting things ready to start the division. It’s also an adaptation period to the culture conditions.

Phase 2: Exponential phase. Once things are ready, the bacteria start multiplying (by binary fission). The metabolic activity on this stage is high and increases as the number of bacteria increases (optimal growth). Some bacteria might die too, but overall, there are more bacteria multiplying than dying.

Phase 3: Stationary phase. This phase is a plateau the bacteria reach because of the depletion of nutrients or accumulation of waste (the acids they produce can inhibit their own activity). Less food means less activity and therefore fewer bacteria dividing. At this point, the growth and death rates are equal, and the overall number of microorganisms remains constant.

Phase 4: Death phase. At this point, nutrients are decreasing and bacteria continue to produce waste from their biological activities (bacterial poop if you may 😉 ). The environment becomes harsh and bacteria start dying (some also go dormant). In this phase, the death rate is faster than the growth rate, so the overall number of microorganisms decreases.

Theoretical growth: it portrays how the curve would continue growing if the bacteria had an endless supply of nutrients.

When you add sourdough starter to your dough, the exponential phase will be much longer because the bacteria:nutrients ratio is much larger. The curve would, to certain extent, follow the theoretical growth because there are lots of nutrients!

How does this apply to your sourdough starter?

Knowing in which phase your starter is, will be very helpful for your baking. The fermentative power of your sourdough will depend on the phase of the cycle it is on, and it is different in each phase.

Although the by-products of the fermentation are essentially the same in each phase, the aromas developed in the bread will be substantially different because every time we take some starter and mix it with flour and water, we’re resetting the growth curve. It starts again in the lag phase.

And depending on the length of the lag phase, more/fewer aromas will build up in the dough. Ideally, we should use the starter at its peak of activity. Which means the lag phase will be shorter.

But, what exactly is the peak of activity and what’s the best way to know it? Let’s dive deeper into this!

The peak of activity and what it means

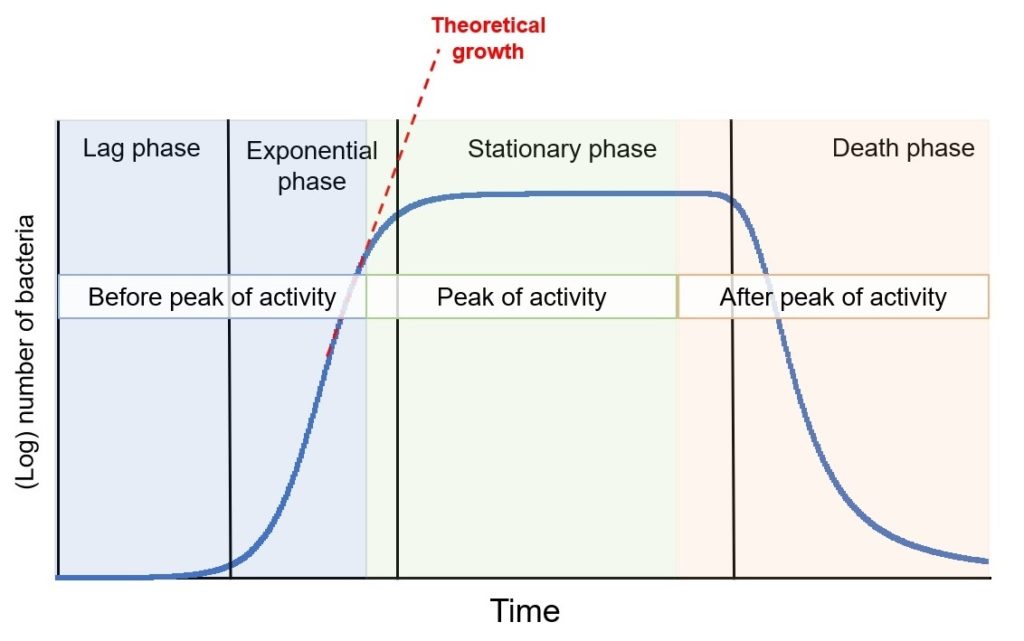

When it comes to sourdough it’s common to talk about the “peak of activity”; we understand that it represents the optimum conditions of the starter and it will work faster if it’s at the peak.

Based on the growth curve I showed you before, it’s easier to see that the peak of activity happens at the end of the exponential phase and throughout the stationary phase. During that time the sourdough starter is very active because 1) the number of alive bacteria is high because they still have lots of nutrients and 2) they’re all used to the environmental conditions, well past the lag phase where they’d be creating “waste” but not multiplying and growing.

Obviously, we are not going to do a bunch of experiments to determine when we should bake. However, once we’re familiar with our starters, we know when they reach the peak of activity (more on this later). We can, then, differentiate 3 stages in our starter:

1.- Before the peak of activity

2.- At the peak of activity

3.- Past the peak of activity

The dough fermentation will definitely be affected by the stage of the starter. Let’s analyze it a bit more how that translates into flavor and aromas of our bread and how it’s related to the growth curve.

The starter has not doubled yet after the last feeding

When we refresh our starter (or when we’re building the levain) what we’re doing is resetting the bacterial growth curve. The microorganisms need to adapt to the new conditions first (lag phase) and then eat and multiply (exponential phase).

If your starter has not even doubled since the last feeding, the microorganisms didn’t have enough time to reproduce; they are at the very beginning of the exponential phase and there is still a low number of them.

Basically, you’d be adding just flour and water with a low number of bacteria.

At this point, the fermentative power of the starter is not high enough because there aren’t enough bacteria to perform the job; which means your dough will need a longer time to ferment. This can be detrimental to your dough because longer fermentation times might lead to a more acidic dough.

Not only that, but you could also risk destroying the gluten network. If the fermentation is much longer than it should, your flour might not be able to resist and the gluten strands will start to deteriorate.

Maybe, flavor-wise, the bread turns out as tangy as you like it, but the structure could be compromised.

The starter has reached or almost reached the peak

People recommend using the starter at its peak of activity, but what many don’t know it’s why exactly this is the best condition for sourdough baking. Spoiler alert: It has nothing to do with your culture being hungry.

At least, not in the literal sense of the word, because the microorganisms eat when they have food, and when they don’t, they just change their metabolism pathway and go into “survival mode” (they become dormant). That’s why they can survive in the fridge for months without being fed, or they can be frozen or dried.

Every time we change the environment of the microorganisms, they need to adapt to the new conditions; so, they have to go through the lag phase again. If the starter has passed the peak or if it’s too early in the feeding cycle, this adaptation period is going to be longer. Either because the microorganisms need to get ready to increase the colony, or because they went into survival mode.

The idea of using the starter at the peak of activity is to reduce the lag phase as much as possible. Because longer lag phases can bring undesired aromas or weaken the gluten network.

The reason the bacteria are very active at this point is that they don’t have to use energy to get ready to multiply, and they’re not getting dormant or dying at a higher rate because there’s still plenty of nutrients.

A change of environment can be anything that makes the new conditions different from the culture. For example, adding salt to your dough, adding more/less water, adding more/less wholemeal flour, adding sugar, adding fats etc.

The starter passed the peak and it’s collapsing

If your starter has reached the peak and has started to collapse, it means that it’s either at the end of the stationary phase or at the beginning of the death phase already, and it already has accumulated a significant amount of fermentation by-products.

Among these by-products, there are several organic acids responsible for the acidity of the sourdough (lactic acid and acetic acid are the most common). If you used this starter, the fermentation would be slower at the beginning because:

1.- There are less alive bacteria, since many might have died already

2.- The acidification of the starter can inhibit the growth of the bacteria, so the fermentative power will be weaker. The extent of this inhibition depends on how acidic the starter became. That’s why when we try to revive a forgotten starter, it might take a couple of feedings until we see some activity.

3.- The bacteria that are still alive need a longer lag phase before they start growing again. During this lag phase they will get ready for the new environmental conditions (your dough) and will fix the pH of the dough that turned too acidic. And remember, during this phase, bacteria keep producing acids but they’re not reproducing.

Basically, if you don’t control de fermentation, your bread can be very sour. Once again, remember that longer fermentation times not only affect flavor, but also the structure.

Contrary to what many people think, though, you can still use a starter that has passed its peak of activity (by just a few hours) and still obtain a bread that has not soured too much, as long as you control the fermentation.

But.. What if I like my bread very tangy?

The sourness of sourdough bread comes from accumulated organic acids in the dough. So, in order to get the tangy flavor, we need to ensure that the dough has accumulated enough of these compounds.

We can do that by using slightly warmer temperatures during the bulk fermentation. Doing this, the bacteria will be closer to their optimum living conditions, and they will perform a faster fermentation. We could push the bulk a little to get that extra sourness.

How do I know my starter is ready to bake?

There are different ways to check when your starter is ready, and the more familiar you are with it, the easier it’ll be. I’m going to tell you my favorite way to check the peak of activity at home: The height test

I don’t know if this is how people know it, but it’s how I call it. The height test is, in my opinion, the most reliable way for the home baker to check their starter.

If you always feed your starter the same ratios of flour and water, or you build your levain in the same way, this test is great for comparisons; it will be very easy for you to know if it’s ready by just looking at how much it grew. It also prevents the “human factor” more than other tests and reduces the chances of making a mistake.

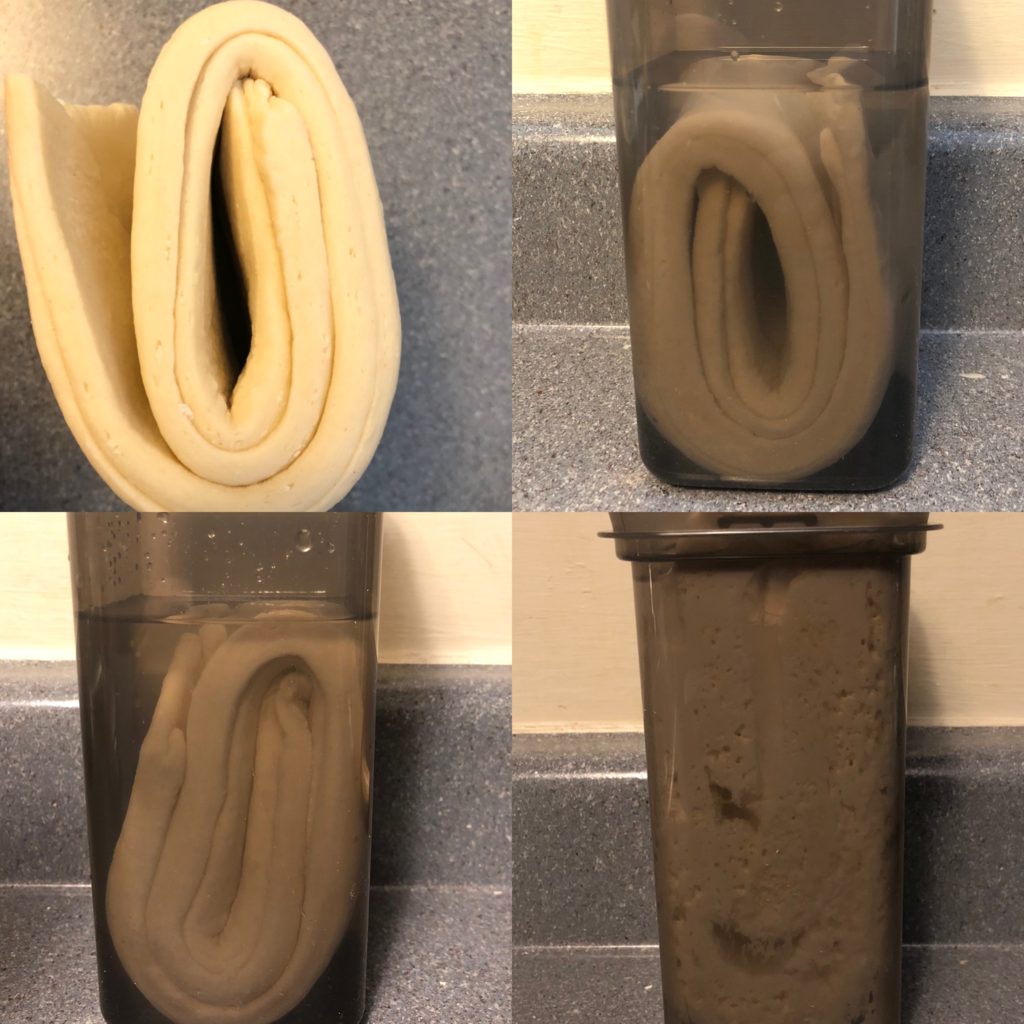

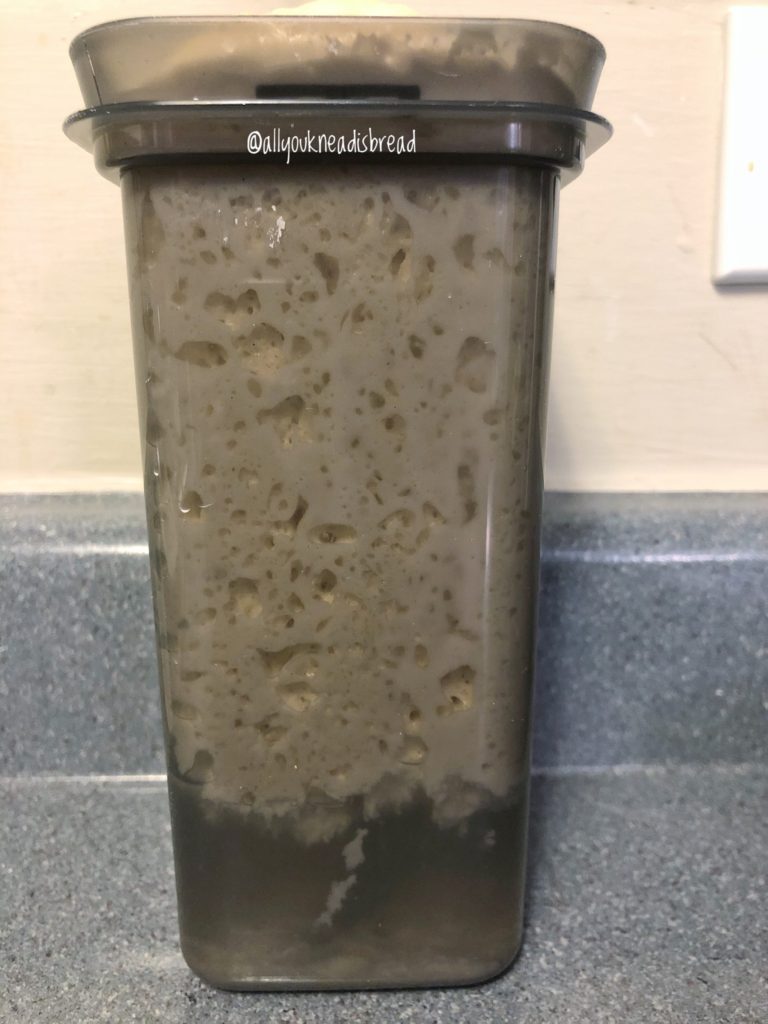

How to perform the maximum height test

As the name indicates, this test is to see how high the starter can grow (this applies to 100% or less hydration, more liquid starters can’t grow too much, for obvious reasons). The peak of activity coincides with the maximum height.

After reaching the maximum height, the starter will remain at that height for a few hours (stationary phase) before it starts collapsing (beginning of the death phase)

Let’s say you feed your starter with a 1:1:1 starter:water:flour ratio. Then you let it ferment and record the height (taking pictures might be even better!) after it reaches the maximum height you need to pay attention to how long it stays at that height and when it starts collapsing.

Imagine that right after feeding, your starter takes 5 hours to reach the highest height, and then it stays 2 more hours at that height. Those last 2h will be the best period to use your starter.

By doing this simple test, you will see how much your starter grows (double, triple, quadruple?). It’s important to know the temperature when you do this little experiment because in warmer days, your starter will grow faster. However, since you know more or less the highest height it will reach, you just need to keep an eye on it!

Always remember that the time your starter takes to grow will depend on the temperature of your kitchen. Warmer temperatures will make the starter more active because they’re close to their optimum growing temperature. Colder temperatures will make the starter grow slower, because these are far from the optimum conditions.

Let’s wrap this up

I’d like to finish my first Bread Science Fridays by highlighting a few concepts:

1.- Bacterial growth has four phases that can be applied to our sourdough starters. Knowing what happens in each phase will help us understand our starter.

2.- The starter works best when it’s used at its peak of activity because we’re reducing the lag phase and bacteria can use the energy more efficiently.

3.- The maximum height test is an easy experiment to know when a starter reached the peak of activity. It’ll help you understand at which phase your starter is and when it’s best to use.

I hope with today’s post you can understand better your starter and have a better idea of the science behind it! Isn’t the world of sourdough so amazing???

As always, if you ever have any doubts or would like me to talk about the science of something, let me know and I’ll try my best to answer your questions!

You can find me on Instagram or Facebook and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

Happy Bread Science Friday!

Maria

Troubleshooting my lievito madre

The time has come! After several tests and experiments, I can 100% confirm that my lievito madre (or pasta madre, or LM or PM, you’ll see both in this post) is healthy and ready for the “grandi lievitati”!

This is a long post, so buckle up! Get some water, a couple of snacks, and let’s get to it!

In this post, you will find all the problems that I encountered with my pasta madre and how I fixed them one by one. You will also learn how certain factors affect the pasta madre and why from a scientific point of view.

After four months of insanity over the wellness of my lievito madre I have finally brought it back to full strength. It’s been a long journey full of troubleshooting and note-taking. I can now conclude that it wasn’t a single problem that was causing the LM to be weak, but several that I had to fix one by one.

A few pointers and clarifications

I started the LM with fermented apple water and from there I built a liquid starter (100% hydration). Then I converted it into a 35% hydration starter. You can check this post to see how I did it.

I’d like to remark that Pasta Madre is not just a stiff starter, it’s a low hydration stiff starter with very particular maintenance conditions and a very specific way to prepare it for baking. This method promotes very specific strains of bacteria and yeasts in a very specific ratio to keep a very specific pH.

Pasta Madre has an incredibly strong fermentative power that’s able to ferment dough with an incredibly high amount of sugar, butter, and egg yolk (substances that can inhibit the growth of bacteria and yeast and hinder gluten development)

Panettone, Pandoro, and Colomba di Pasquale are the holy trinity of pasta madre baking. They undergo long fermentations that due to the specific methods designed for pasta madre, the dough does not develop any acidity.

Pasta madre vs stiff starter

For example: If you’re reading this, I’m pretty sure you’re familiar with “the lievito madre must triple in 3-4h at 28C three consecutive times before it’s ready to make panettone”

If your lievito madre can do that, then it’s mature and ready to prepare the primo impasto (the first dough). However, let’s say that you prepare a stiff starter at 60% hydration. If you compare this stiff starter with pasta madre, you put both in a chamber at 28C and let them ferment, I assure you the fermentation speed will be COMPLETELY different.

Therefore, the “triple in three hours” rule for the pasta madre cannot apply to this 60% hydration stiff starter. And the triple in 12h rule for the primo impasto will not apply either because a 60% stiff starter does NOT behave the same as Pasta Madre. Keep in mind that artisan recipes and methods to make Panettone the Italian way are designed to be used with Pasta Madre.

Let’s start from the beginning

When I first started my LM I was using W380-400 Manitoba flour from Molino Caputo, but I ran out if it and I had to buy more. The new flour I received was W400 Manitoba flour from Molino Grassi.

When I changed the flour, the first thing I noticed was that the new flour needed more than 35% of water. It was impossible to incorporate all the flour. So, I started to add a little more water. Until I was using 40% of water. That extra 5% messed the whole bacteria/yeast ratio. Why? Let’s talk about “water activity”.

Water activity and what it means in food

In Food Science, water activity is a very important concept. The FDA defines water activity as “the ratio between the vapor pressure of the food itself, when in a completely undisturbed balance with the surrounding air media, and the vapor pressure of distilled water under identical conditions”.

The water activity of pure water is 1 and it’s the maximum possible value in a 0-1 range.

In essence, water activity is a way to quantify how much water there is in a particular sample, and based on that number we know which microorganisms could grow in that sample. This is particularly important for all fermentation operations, shelf-life studies, etc.

Water activity in my lievito madre

Back to my pasta madre; now you understand why that extra 5% of water I was adding created an unbalance between the Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and the yeasts in the culture. The water activity changed and it either promoted other strains of bacteria to grow or a faster proliferation among yeast strains. Or maybe even both things happened.

What was clear was that the higher water activity wasn’t promoting the best environment for the microorganisms that should be in lievito madre. In a healthier LM this wouldn’t have been such a problem, but there were other factors affecting it.

Problem #1: Alterations in the water activity of the lievito madre

Cause of the problem: impatience while incorporating flour

Solution: patience! I started to let the PM rest for a few minutes after I managed to incorporate the flour. Like a little autolyse. I went from needing 40% of water and struggle to a 35% and no problems.

Effect of flour in my lievito madre

As I mentioned, I had to change the flour I was using because the website I was buying from changed the supplier. The new flour was SO STRONG! Strong flour must be the best for panettone, right? WRONG.

Manitoba flour comes from a type of hard wheat with higher protein content. However, in order to have that high protein content, the flour has to be very refined and stripped off as much bran as possible. But this process also takes some of the nutrients of the flour away. Nutrients that the bacteria need to be able to perform their biological activities… See where I’m going?

It seemed as if my LM wasn’t getting enough nutrients every time I refreshed it, which caused a progressive loss of fermentative power. I was, unknowingly, starving my LM to the point of almost zero strength.

The smell told me there was some fermentation going on, probably from the yeasts, but it barely grew, it didn’t have the crumb-like inner structure, and it didn’t even float in the bath after 24h.

Problem #2: starvation of my LM

Cause of the problem: lack of nutrients in the flour.

Solution: A mix of flours with a less refined flour that would provide more nutrients.

Lack of nutrients in the flour

Talking to my friend Kel (@wonky.loaf.of.sourdough), she pointed out that maybe the flour was, indeed, too refined. And she was right! That night, when I was about to throw away the LM and start from scratch, I decided to do one last experiment. I refreshed the LM and put it in the fridge, and with the discards, I created a sibling, which I fed 80% of Manitoba flour and 20% of King Arthur bread flour.

In about 12h it was floating and showing signs of life. 12h is a long time, but previously, my LM wouldn’t float after 24h. So, this was clearly the 1st win!

Since that moment I always feed my LM a mixture of flours. I tried 15% of bread flour but it showed lower activity, and I tried also 25% of bread flour but after a feeding cycle I lost a lot of LM, it disintegrated very fast. Once I ran out of bread flour, I started to use King Arthur High Protein flour or King Arthur AP flour, whichever I had at the moment.

The second feeding went even better, in 3-4h it was floating and happy. It smelled so well, it was spongy, it was getting healthier! Or so I thought… It was better, but not 100% there. While this was definitely the major problem, there were still lots of things I wasn’t doing right.

Small changes made all the difference

I used the LM to bake a few loaves and it worked well. I tried to make sandwich bread and the dough rose well too. But when I used it to make brioche it was extremely difficult to incorporate all the butter. This is usually a sign that something is not right.

I also noticed that the loaves I made with LM had large lumps that didn’t disappear after baking. The dough wasn’t absorbing the LM and it wasn’t fermenting, because the lumps didn’t puff up while baking.

At this point I was using the 80-20 mix of flours, 35-37% of water and I was rolling the dough with my pasta maker. The temperature of the house was around 66-69F. The temperature was adequate, the flour was adequate, the hydration was adequate…

Again, Kel to the rescue! She suggested that maybe I was rolling the dough too thin and I was working the gluten too much.

The reason I was rolling the dough with the pasta roller was plain laziness! At this point I had been refreshing the PM once a day for several weeks, it became a tedious task. The pasta maker made the process much faster, but I was compromising the gluten.

Effect of gluten in my lievito madre

The temperature, flour mix, and hydration were good, and in the conditions necessary to promote proper fermentation. However, the dough structure also plays a role.

When I started to roll the dough with the pasta maker, I developed to gluten too much. To the point were 1) the dough was too thin and extremely elastic, making it easier to roll it very tight before putting it in the water bath, and 2) the gluten was so developed that after a feeding cycle, the part touching the water was degrading much faster.

I believe that by working the dough with the pasta maker and rolling it too tight, the oxygen availability in the core of the LM was low, which probably led to a proliferation of yeast and a change in the metabolic pathway of the microorganisms; which led to the development of a different aroma profile and higher production of acetic acid. It was making the dough sourer than it should.

Gluten structure vs development of aromas

A tight LM also meant that all the volatile components released during the fermentation didn’t have a place to go, the dough was so tight that they couldn’t move much and they probably were kept in the core of the LM instead of flowing into the water bath. This too increased the acidity of the pasta madre.

The part that was touching the water, disintegrated much faster. The layers were so thin that after a few hours in the water they dissolved. So, the center part was too dry and the outer part too wet.

I learned that rolling the dough too thin and too tight is detrimental to the dough in the long run. At the beginning you might not feel the difference and the smell changes so very slightly that you don’t even realize it’s becoming sourer.

Once I started to roll the dough by hand, the smell started to change, and it got much better in just 2 feeding cycles. The looser structure helped the LM develop a much better crumb-like core.

Problem #3: The dough was still showing signs of weakness and the smell wasn’t great yet

Cause of the problem: machine rolling affected the fermentation by affecting the gluten structure.

Solution: go back to hand rolling

Effect of maintenance temperature

I had spent 4 months like a doctor trying to figure out the disease of the patient. I didn’t know what was happening, so I started to rule things out. At this point I was pretty confident the LM was healthy, and the best way to test how the LM is doing is by trying to make panettone.

Everything was looking right, the hydration, the flour, the rolling method… the house temperature was a bit higher but it shouldn’t be a problem, should it? WRONG but I didn’t know it yet…

One day I woke up early, I had done the bagnetto the night before, and I started to do the 3 refreshments to prepare the LM for panettone. So that day I prepared the primo impasto and let it ferment for 12h at 28C.

At most, the primo impasto should take 14h to triple. But mine barely doubled in 15h

Obviously, my lievito madre was not ready yet. I should have known, as 4h after the last refreshment it wasn’t even floating, it hadn’t tripled in size either, but I was so eager to try to make panettone that I ignored the signs. I didn’t proceed with the secondo impasto, there was no point (I made waffles with the dough, there’s no dough that a waffle maker can’t fix!)

Effect of pH on my lievito madre

After the panettone fail, I decided to taste the LM on each refreshment (I should’ve done it earlier and more often), it was the only thing I hadn’t test yet, the flavor. And OMG! The dough did smell acidic but nothing too weird. But the taste? It was spicy, vinegary… it was super sour!

As it appears, those warmer days, once again, disrupted the equilibrium between bacteria and yeast during the maintenance refreshments. And I believe the warmer temperatures helped in the proliferation of yeasts that led to a drastic increase in the production of acetic acid and a pH unbalance.

pH is one of the factors that affect the survival conditions of the microorganisms. If the pH changes, so will the strains of microorganisms that can grow in that environment.

In need of a deep cleanse

The LM needed to be purified. I decided to do a bagnetto and then I proceeded to do the refreshment as usual. But this time I added 4% of egg yolk to buffer the acidity and help reestablish the microorganism colony. It worked wonders! (This is a technique suggested by Italian Maestros)

I only used egg once, the following days I only use flour and water and I made sure the water bath was at 4C so with the warmer temperature in my house I could keep the LM temperature at bay. The acidic taste got milder and milder until one day I tasted the LM and it was just PERFECT. It had a hint of acid, and a hint of sweetness.

The smell was HEAVENLY. It smelled alcoholic, but with a little bit of acetic acid, and something sweet. Overall it was a very very very pleasant smell. The kind of smell that you just know is right.

Problem #4: a drastic pH change

Cause of the problem: higher temperature during maintenance feeding cycles disrupted the yeast:bacteria ratio again.

Solution: purification step with egg yolk in one refreshment and cold water for the bath to compensate for the warmer temperatures.

Finally: the panettone test

I tried to make panettone again, this time pretty confident because the smell was SO GOOD that I just knew that was how it was supposed to smell (and taste!)

It was just amazing how much better the LM grew during the 3 preparatory refreshments. Even more so when I made the primo impasto. It barely had any lumps of LM in the dough, and the ones it had were very small. The dough absorbed the butter and egg yolk beautifully! (if the pH is not where it has to be, it’s difficult to for the dough to absorb fats). Even the gluten was formed differently. I could tell the pH of the LM was exactly where it had to be.

I finished the primo impasto at 9:30 pm and left it at 28C overnight. Next morning, just 11h later, it had already tripled.

I cannot express the happiness I felt when I saw it. Every time I try to make panettone, the night of the primo impasto I can’t sleep. I’m nervous it won’t rise. But that night I slept well, because I knew the LM was healthy.

It worked! Panettone on the way!

So that day I proceeded with the secondo impasto and made the panettone. And I cannot tell you how amazing the secondo impasto was. The dough was super silky. I can tell it had been my very best gluten development so far. The windowpane test was just incredible (You can see it on my highlights on my Instagram).

After 4 months of frustration, experimentation, speculation, and research. I can finally say that I brought my LM back to its healthiest life. Actually, not back, because it has never been this healthy before.

If anything, working with my pasta madre has been a humbling lesson and a reminder that this is science. Once I started to work with my pasta madre as I would with a project in the lab, things started to change, I started to see the problems and mistakes I was making. And I’ve learned so much!

Acknowledgements

If you’ve made it this far, I’d like to thank you for reading all this. And if you’re struggling with your pasta madre, I hope my experience can help you in your journey.

Also, I’d like to say thank you so much to all of you who followed this journey and gave me ideas or simply asked about my LM. Brainstorming with others is always better! And thank you to my friend Kel. Without her nerdy mind, I probably wouldn’t be here today, with a healthy pasta madre!

#missionpanettone is now stronger than ever!!!

Happy baking!!

Maria

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.

Sourdough Blueberry Muffins

Two words: blueberry muffins. It can’t get better than that. Nah, it can, with sourdough it can! Sourdough blueberry muffins, my friends!

I’m determined to use all my sourdough discards, it is painful to throw it away! So these days the new normal is something like this:

Feed starter – save discards – bake loaf -bake with the discards

The more I bake with sourdough discards, the more I get to test the effect on other food. So far, I can say that cakes and muffins made with sourdough last longer than those without. Nothing new really, sourdough bread also lasts fresh longer time

Isn’t it amazing? Although… after you make these muffins, I doubt you’ll need an extended shelf life, they’re INCREDIBLE!

Why do sourdough baked goods last longer?

Bread and other baked goods are usually discarded when they lose quality rather than when they get spoiled. Bread gets stale kind of quickly, cakes dry and get crumbly… Although there are many factors involved in why and how baked goods dry out, obviously, moisture content plays a key role.

When you mix your ingredients with water, the very first thing that happens is that those ingredients absorb the water. They start making hydrogen bonds and trapping the water within the matrix. Sugar and salt start dissolving, gluten proteins start hydrating, starch granules starch absorbing water and swelling (you see why autolysis helps to develop the gluten? Wink wink)… And all this takes a long time. Much more time than we think.

If we focus on the physical changes of food, rather than the biological changes of sourdough fermentation, we need to pay close attention to how the water is used in baked goods.

Moisture is key

There are two types of water in food: the bound water that’s forming some type of bond and the free water, that is simply stored within the food matrix.

After baking, the free water is going to be the first to go. It moves from the inside of the food (The crumb) towards the outside. Thus, why crust gets soggy over time, and then it finally evaporates and leaves the food.

Bound water, however, it’s somewhat trapped. It can be part of the gluten network, of swollen starch granules, it can be trapped within the fat matrix etc. The amount of bound water (among other things, of course) is one of the things that determines how long the food stays fresh; because its’ much more difficult to separate from the other ingredients. So the loss of quality related to water is slowed down.

Since sourdough baking needs lots of time, the levain preparation, long fermentation times etc. allow all ingredients to keep absorbing water and binding it to other molecules. The flour had many hours to ensure al the particles are saturated with water (I’m assuming a 100% hydration starter here). These bonds survive throughout the whole process; after the food is baked and starts cooling down, the food holds onto these water bonds.

And that’s one of the reasons food made with sourdough lasts longer!

If you’re interested in other food science facts, feel free to send me an email or DM on social media and I’ll try my best to write a post about it!

Back to the muffins!

Alrighty! About these muffins… I made them small for two reasons: 1) because the number of muffins I eat doesn’t depend on the size, so I’d better eat smaller portions now that the gym is close 🙂 and 2) because I don’t have a large muffin tin and if I buy more kitchen stuff my husband is going to make me sleep in the kitchen.

So obviously, feel free to make larger muffins or smaller. Whatever you prefer!

I like to whip eggs and sugar very well, this helps with the airy structure of the muffin and I think the texture turns out super delicate!

Usually, when you make blueberry muffins, they collapse a little after they come out of the oven, it’s normal, that’s because the water inside of the fruits turns into steam while the muffins are baking, and they swell. Some blueberries might burst, and the others, when they cool down, they collapse because the steam condenses. They also wrinkle because the heat affects the structure of the skin.

I like to let the batter chill in the fridge for at least a couple of hours to allow the baking powder and baking soda hydrate well. Their leavening power is activated by acids and moisture. You can leave the batter in the fridge overnight and bake the muffins first thing in the morning!

If you make this recipe, let me know what you think and tag me on your creations! I love to see what you guys do!

You can also follow me on Instagram or Facebook and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

If you have any suggestions or would want me to make some recipes, adapt a yeast-based recipe into a sourdough one, etc, please contact me and I’ll try my best to respond and plan a recipe!

Happy baking!

Sourdough blueberry muffins

Use your sourdough discard to make these delicious muffins!

Ingredients

- 200 g all purpose flour

- 200 g sourdough discards (collected throughout a week)

- 1/2 tsp baking soda

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1 pinch salt

- 3 L eggs

- 180 g caster sugar

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 1 tsp lemon extract (optional- to taste)

- 180 g heavy whipping cream

- 60 g olive oil (see notes)

- 1½ cups blueberries

Instructions

-

Preheat your oven at 375 F

-

Sift the flour into a large bowl. Take a tablespoon of that flour and reserve

-

Add the baking soda, baking powder and salt to the flour and combine

-

In the bowl of your stand mixer whip the eggs until they are fluffy and have a light yellow color

-

Add the sugar to the eggs and combine

-

Add the whipping cream, the oil, the sourdough starter, and the extracts and combine well. Use a spatula if you need to break down the sourdough blob

-

Change from the wire whisk to the paddle attachment, add the flour in 3 batches and combine at medium-low speed

-

In separate bowl toss the blueberries and the tbsp of flour you reserved and carefully stirr tso they blueberries get a nice coat of flour

-

Add the blueberries to the batter and with a spatula stir until just combined (you can put now the batter in the fridge if you want)

-

line a muffin tin with baking cups and fill them to about 3/4

-

Add some blueberries on top as decoration

-

Bake for about 30 minutes or until they have a nice golden color

Recipe Notes

I like to use olive oil because I think it gives muffins in general a really nice aroma. And it’s also how my mom taught me. But feel free to use melted butter or any other oil of your choice!

If you don’t have blueberries, you can make these muffins with any other fruit

How to do the 3 preparatory refreshments for panettone

The first thing to make panettone is to create the lievito madre (LM from now on 😉 ) and then what? Then we need to make sure the LM is ready, strong and not acidic before we mix the panettone dough. We achieve this by doing the bagnetto followed by the 3 preparatory refreshments.

To learn how to create a lievito madre from scratch check this post

Why do we need the bagnetto?

This technique is a way to purify, oxygenate and release of acidity the LM. It consists of a warm bath where we’ll put the LM for 30 minutes. Depending on its behavior, we can assess how our LM is doing. If it’s too acidic, if it’s too weak, or if it’s just good to go!

When do we do the bagnetto?

Only in two cases

- Before every maintenance refreshment

- Before the 3 preparatory refreshments for panettone

We shouldn’t overuse this technique because it will weaken our LM if we do it too often, as an exception, if you’re in the same situation as me, I built up my LM in 19-20 days instead of 15. If during those days you suddenly feel a change in your LM and you think it’s smelling much more acidic than the day before (if you can actually measure the acidity that would be even better), you can do a bagnetto, just make sure that you leave at least 2 days between this bagnetto and the bagnetto before the 3 refreshments.

How to do the bagnetto?

This is the procedure:

- Fill up a large bowl with water at 38C/100F (it must be 38C/100F)

- To the warm water add 2g of sugar per liter of water and stir until it’s completely dissolved.

- Proceed to remove the LM from the container, drain the water, remove the mushy part and squeeze very well.

- Place the LM in the water bath and leave it there 30 minutes

Depending on the state of our LM, three things can happen now:

- Your LM floats right away: you either didn’t squeeze it well to remove all the air trapped inside or your LM is too weak.

- Your LM floats after 5-10mins (or within the bagnetto time, mine floated has floated between 7 and 15 mins): it’s perfect. It’ll start showing only the tip and by the end of the bagnetto more of it will be out of the water.

- Your LM doesn’t float after 30 minutes: It’s too acidic, it doesn’t mean it’s weak, it means there is lots of bacterial and yeast activity.