Welcome to a new section of my blog: Bread Science Fridays! In this section I will be indulging on my nerd side and talk about the science of many things behind your beautiful bakes. This week’s post is dedicated to our beloved sourdough starters and the science behind them!

Ever since the pandemic started, more and more people jumped into sourdough. So, I thought it could be fun to explain scientifically what happens when you feed your starter (or build your levain).

A sourdough starter it’s just a culture of microorganisms that are alive and perform their own biological activity. These cultures are composed, mostly, by different strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), saccharomyces yeasts, and some candida yeasts among others.

In this post, you will learn the phases your starter goes through during a feeding cycle, why using your starter at its peak of activity is important, and the science behind it!

A couple of things about biology

In microbiology, a strain of a certain type of microorganism is like a subtype of named microorganism. For example, the lactic acid bacteria type would be the lactobacillus but there are many subtypes (Strains). Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Lactobacillus Sanfranciscensis, Lactobacillus Reuteri… They’re all LAB but with some differences (from shape to optimum living conditions).

Each strain has its specific optimum living conditions. That is the optimum temperature, water activity, pH… that will make the fermentation rate the fastest. The fact that a microorganism is “happy” at 28C, for example, doesn’t mean that it cannot perform its biological activities at 29C or at 20C. It means that the performance will not be the best. As you know, it slows down at cold temperatures. However, it’s higher temperature that pose a threat to the microorganisms. Too high temperatures will inhibit and eventually kill the bacteria.

The bacterial growth curve

Bacteria, as living organisms, grow, multiply, and die. The reason our sourdough starter is resilient is not because the bacteria are indestructible, its’ because there are millions of them and not all of them are the same age. They are in different growth phases. While maybe most of the bacteria are dying, some might have just been born.

Bacteria and yeast multiply by dividing themselves into two. 1 becomes 2, 2 become 4, 4 become 16, etc. This mechanism is called binary fission. Therefore, their growth is exponential. In microbiology, this growth is depicted using growth curves.

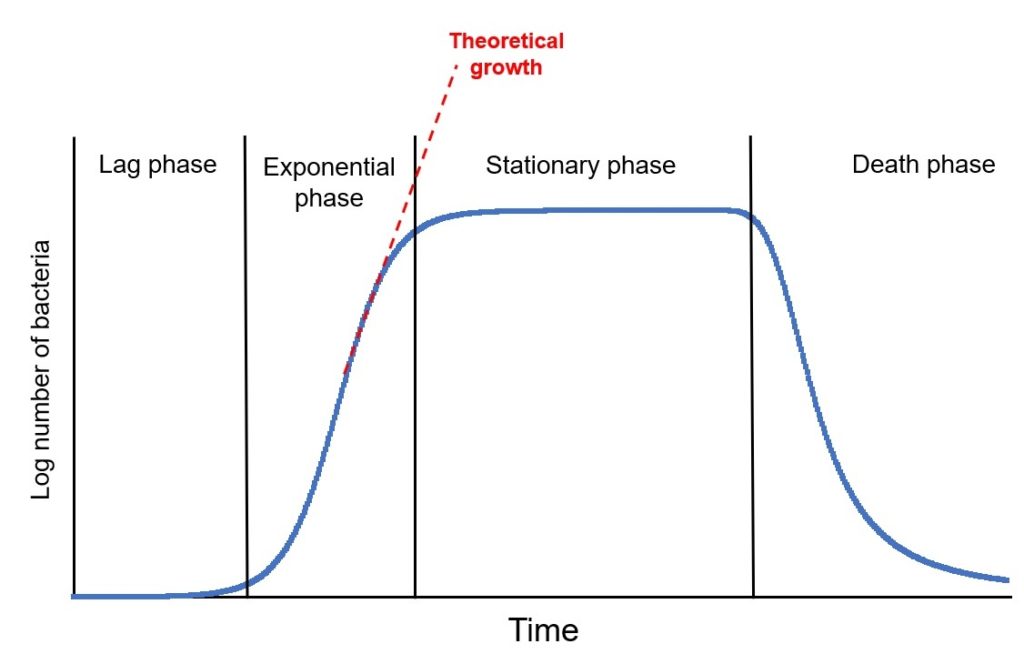

Bacterial growth curves are specific for each strain of bacteria in a specific set of conditions (Changing the temperature will change the curve). In these curves we can see the 4 phases bacteria undergo from the moment they’re born to the moment they die. A generic bacterial growth curve would look similar to this one:

Our starter will follow this growth cycle too. Understanding what happens in each phase will help us understand our starter and when we should use it for baking to prevent a excess of sourness

The phases explained

Phase 1: Lag phase. This is the very beginning of the curve. At this stage, the microorganisms have enough nutrients and are active but they’re still not multiplying. What they’re doing is synthesizing proteins and getting things ready to start the division. It’s also an adaptation period to the culture conditions.

Phase 2: Exponential phase. Once things are ready, the bacteria start multiplying (by binary fission). The metabolic activity on this stage is high and increases as the number of bacteria increases (optimal growth). Some bacteria might die too, but overall, there are more bacteria multiplying than dying.

Phase 3: Stationary phase. This phase is a plateau the bacteria reach because of the depletion of nutrients or accumulation of waste (the acids they produce can inhibit their own activity). Less food means less activity and therefore fewer bacteria dividing. At this point, the growth and death rates are equal, and the overall number of microorganisms remains constant.

Phase 4: Death phase. At this point, nutrients are decreasing and bacteria continue to produce waste from their biological activities (bacterial poop if you may 😉 ). The environment becomes harsh and bacteria start dying (some also go dormant). In this phase, the death rate is faster than the growth rate, so the overall number of microorganisms decreases.

Theoretical growth: it portrays how the curve would continue growing if the bacteria had an endless supply of nutrients.

When you add sourdough starter to your dough, the exponential phase will be much longer because the bacteria:nutrients ratio is much larger. The curve would, to certain extent, follow the theoretical growth because there are lots of nutrients!

How does this apply to your sourdough starter?

Knowing in which phase your starter is, will be very helpful for your baking. The fermentative power of your sourdough will depend on the phase of the cycle it is on, and it is different in each phase.

Although the by-products of the fermentation are essentially the same in each phase, the aromas developed in the bread will be substantially different because every time we take some starter and mix it with flour and water, we’re resetting the growth curve. It starts again in the lag phase.

And depending on the length of the lag phase, more/fewer aromas will build up in the dough. Ideally, we should use the starter at its peak of activity. Which means the lag phase will be shorter.

But, what exactly is the peak of activity and what’s the best way to know it? Let’s dive deeper into this!

The peak of activity and what it means

When it comes to sourdough it’s common to talk about the “peak of activity”; we understand that it represents the optimum conditions of the starter and it will work faster if it’s at the peak.

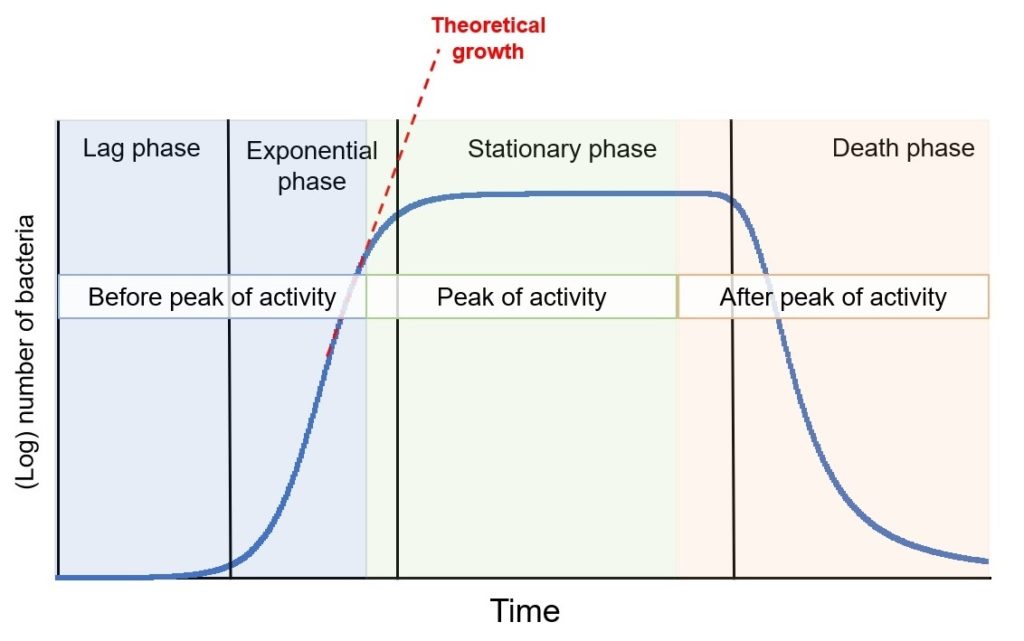

Based on the growth curve I showed you before, it’s easier to see that the peak of activity happens at the end of the exponential phase and throughout the stationary phase. During that time the sourdough starter is very active because 1) the number of alive bacteria is high because they still have lots of nutrients and 2) they’re all used to the environmental conditions, well past the lag phase where they’d be creating “waste” but not multiplying and growing.

Obviously, we are not going to do a bunch of experiments to determine when we should bake. However, once we’re familiar with our starters, we know when they reach the peak of activity (more on this later). We can, then, differentiate 3 stages in our starter:

1.- Before the peak of activity

2.- At the peak of activity

3.- Past the peak of activity

The dough fermentation will definitely be affected by the stage of the starter. Let’s analyze it a bit more how that translates into flavor and aromas of our bread and how it’s related to the growth curve.

The starter has not doubled yet after the last feeding

When we refresh our starter (or when we’re building the levain) what we’re doing is resetting the bacterial growth curve. The microorganisms need to adapt to the new conditions first (lag phase) and then eat and multiply (exponential phase).

If your starter has not even doubled since the last feeding, the microorganisms didn’t have enough time to reproduce; they are at the very beginning of the exponential phase and there is still a low number of them.

Basically, you’d be adding just flour and water with a low number of bacteria.

At this point, the fermentative power of the starter is not high enough because there aren’t enough bacteria to perform the job; which means your dough will need a longer time to ferment. This can be detrimental to your dough because longer fermentation times might lead to a more acidic dough.

Not only that, but you could also risk destroying the gluten network. If the fermentation is much longer than it should, your flour might not be able to resist and the gluten strands will start to deteriorate.

Maybe, flavor-wise, the bread turns out as tangy as you like it, but the structure could be compromised.

The starter has reached or almost reached the peak

People recommend using the starter at its peak of activity, but what many don’t know it’s why exactly this is the best condition for sourdough baking. Spoiler alert: It has nothing to do with your culture being hungry.

At least, not in the literal sense of the word, because the microorganisms eat when they have food, and when they don’t, they just change their metabolism pathway and go into “survival mode” (they become dormant). That’s why they can survive in the fridge for months without being fed, or they can be frozen or dried.

Every time we change the environment of the microorganisms, they need to adapt to the new conditions; so, they have to go through the lag phase again. If the starter has passed the peak or if it’s too early in the feeding cycle, this adaptation period is going to be longer. Either because the microorganisms need to get ready to increase the colony, or because they went into survival mode.

The idea of using the starter at the peak of activity is to reduce the lag phase as much as possible. Because longer lag phases can bring undesired aromas or weaken the gluten network.

The reason the bacteria are very active at this point is that they don’t have to use energy to get ready to multiply, and they’re not getting dormant or dying at a higher rate because there’s still plenty of nutrients.

A change of environment can be anything that makes the new conditions different from the culture. For example, adding salt to your dough, adding more/less water, adding more/less wholemeal flour, adding sugar, adding fats etc.

The starter passed the peak and it’s collapsing

If your starter has reached the peak and has started to collapse, it means that it’s either at the end of the stationary phase or at the beginning of the death phase already, and it already has accumulated a significant amount of fermentation by-products.

Among these by-products, there are several organic acids responsible for the acidity of the sourdough (lactic acid and acetic acid are the most common). If you used this starter, the fermentation would be slower at the beginning because:

1.- There are less alive bacteria, since many might have died already

2.- The acidification of the starter can inhibit the growth of the bacteria, so the fermentative power will be weaker. The extent of this inhibition depends on how acidic the starter became. That’s why when we try to revive a forgotten starter, it might take a couple of feedings until we see some activity.

3.- The bacteria that are still alive need a longer lag phase before they start growing again. During this lag phase they will get ready for the new environmental conditions (your dough) and will fix the pH of the dough that turned too acidic. And remember, during this phase, bacteria keep producing acids but they’re not reproducing.

Basically, if you don’t control de fermentation, your bread can be very sour. Once again, remember that longer fermentation times not only affect flavor, but also the structure.

Contrary to what many people think, though, you can still use a starter that has passed its peak of activity (by just a few hours) and still obtain a bread that has not soured too much, as long as you control the fermentation.

But.. What if I like my bread very tangy?

The sourness of sourdough bread comes from accumulated organic acids in the dough. So, in order to get the tangy flavor, we need to ensure that the dough has accumulated enough of these compounds.

We can do that by using slightly warmer temperatures during the bulk fermentation. Doing this, the bacteria will be closer to their optimum living conditions, and they will perform a faster fermentation. We could push the bulk a little to get that extra sourness.

How do I know my starter is ready to bake?

There are different ways to check when your starter is ready, and the more familiar you are with it, the easier it’ll be. I’m going to tell you my favorite way to check the peak of activity at home: The height test

I don’t know if this is how people know it, but it’s how I call it. The height test is, in my opinion, the most reliable way for the home baker to check their starter.

If you always feed your starter the same ratios of flour and water, or you build your levain in the same way, this test is great for comparisons; it will be very easy for you to know if it’s ready by just looking at how much it grew. It also prevents the “human factor” more than other tests and reduces the chances of making a mistake.

How to perform the maximum height test

As the name indicates, this test is to see how high the starter can grow (this applies to 100% or less hydration, more liquid starters can’t grow too much, for obvious reasons). The peak of activity coincides with the maximum height.

After reaching the maximum height, the starter will remain at that height for a few hours (stationary phase) before it starts collapsing (beginning of the death phase)

Let’s say you feed your starter with a 1:1:1 starter:water:flour ratio. Then you let it ferment and record the height (taking pictures might be even better!) after it reaches the maximum height you need to pay attention to how long it stays at that height and when it starts collapsing.

Imagine that right after feeding, your starter takes 5 hours to reach the highest height, and then it stays 2 more hours at that height. Those last 2h will be the best period to use your starter.

By doing this simple test, you will see how much your starter grows (double, triple, quadruple?). It’s important to know the temperature when you do this little experiment because in warmer days, your starter will grow faster. However, since you know more or less the highest height it will reach, you just need to keep an eye on it!

Always remember that the time your starter takes to grow will depend on the temperature of your kitchen. Warmer temperatures will make the starter more active because they’re close to their optimum growing temperature. Colder temperatures will make the starter grow slower, because these are far from the optimum conditions.

Let’s wrap this up

I’d like to finish my first Bread Science Fridays by highlighting a few concepts:

1.- Bacterial growth has four phases that can be applied to our sourdough starters. Knowing what happens in each phase will help us understand our starter.

2.- The starter works best when it’s used at its peak of activity because we’re reducing the lag phase and bacteria can use the energy more efficiently.

3.- The maximum height test is an easy experiment to know when a starter reached the peak of activity. It’ll help you understand at which phase your starter is and when it’s best to use.

I hope with today’s post you can understand better your starter and have a better idea of the science behind it! Isn’t the world of sourdough so amazing???

As always, if you ever have any doubts or would like me to talk about the science of something, let me know and I’ll try my best to answer your questions!

You can find me on Instagram or Facebook and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

Happy Bread Science Friday!

Maria

Hi thanks for the article.

I’m wondering why the feeding rate and reaching time to stationary phase are not proportional?

Interesting, but you constantly refer to the bacteria, and rarely mention the yeast except at the beginning, yeast and bacteria have different growth patterns and multiply differently. Why is the concentration on just bacteria?

I mostly talk about the bacteria because the ratio is much higher than the yeast (10:1 to 100:1) and also to avoid making the reading a bit annoying, I was hoping people would assume that I meant both microorganims. However, the shape of the growth curve is similar for both, yeast also has the 4 phases, they might be longer or shorter but the generic curve still applies.

My goals or to use this little sweetening as possible in my baking and to have a sourdough bread product that is less sour.

Can you please clarify for me what I need to do to create or maintain a sourdough starter that is on the sweeter rather than more sour side?

Additionally you’re beautiful little video showing the multiplying of the starter indicates to me that at peak performance, the starter has not doubled but has more like quadrupled. Is that an accurate understanding of the process?

I do not want to waste starter, so when I am baking less, can the starter be frozen and then thawed and fed when I’m ready to use it?

Hi Diane!

Typically liquid sourdough (100% hydration) tends to be a bit sourer, however. If refreshed properly and used at the peak, you shouldn’t be adding much of the sour by-products to the dough. Then, when you make bread try to not overdo the bulk fermentation and keep the bread in the cold maximum of 12h (overnight). My “trick” for shorter bulk is to develop the dough by kneading as fast as possible (always being careful not to break the gluten) and then just letting it ferment for up to 5h (20% starter and the time depends also on the temperature). You can start the bread in the evening, put it in the fridge when you go to bed, and bake in the morning. If that’s still too sour for you, you can try to make a stiff starter (a starter at around 50% hydration) and use it instead of the liquid sourdough. Stiffer starters tend to be less sour but they still carry sourdough aromas, you need to find the balance that works for your taste 🙂

Depending on the ratio of flour and starter, the type of flour or blend used etc. The starter can double, or triple or quadruple or barely grow if it’s too liquid (125% hydration or something like that). For a regular 100% hydration, I’d try to record the highest height it rises and that will be your peak. the sourdough rising is the effect of the fermentation, but also the gluten structure. If you’re using a whole meal, gluten free flours etc. the starter might not rise that much, if any.

You can keep your starter in the fridge for months. I’d recommend keeping it in the cold than freezing it. Hope this helps!

Hi Maria, very interesting article. So would you suggest refeeding a starter at it’s peak/stationary phase?

Hi Nelson! Thank you 🙂 Yes, feeding your starter (or any sourdough) at the peak means that the bit of dough you take is going to have the max number of active bacteria and it’ll keep powerful over time.

This is really cool. So one additional component I’m trying to figure out is the number of feedings it takes to reach the point of diminishing returns.

Many bakers say you need to feed your starter several times, some say as much as 10 times, twice a day for 5 or so days, before it’s at absolute peak performance for your dough. If you have a bakery and never refrigerate your starter, this is fine, as your continuously feeding and using. But what about for the once a week home baker?

I use my starter, put it in the fridge where it’ll sit for a week. The night before I bake, I’ll take it out and feed it. If I do 1:1:1 it has already entered the death phase by morning so I’ll opt for 1:3:3, this usually results in the stationary phase by morning.

Then I feed it 1:1:1, wait for the end of exponential, and use in my recipe (during this time I’m also autolysing the bulk of my dough but that’s another story).

The more I feed it 1:1:1 during the stationary phase theoretically the higher % by weight of living bacteria. So how many of these peak feedings are required before you hit that point of diminishing returns?

Significant difference between the first and second feedings, makes sense. What about second to third? How in the world could feeding #10 be any better than #9?

If I’m going to add my starter to the dough on Saturday, is feeding it Friday night and Saturday morning (2 feedings) as active as say taking it out Friday morning and doing 4 feedings?

Basically trying to maximize living dividing bacteria while minimizing feedings and discard.

What are your thoughts?

Hi Collin, this is a very interesting topic indeed! The truth is that it depends on the conditions of each starter. Someone living in the tropics might need to feed their starter more often if using 1:1:1 or just use higher ratios (1:10:10 or 1:15:15). In my opinion, overfeeding can result in less number of active bacteria if you feed your starter too soon (before it got to the stationary phase). In my experience, my starter works better with 1:1:1 or 1:2:2 during winter months, and during summer, if I want to use my starter in the morning, I feed it the night before 1:10:10 and the humidity and warmer temperatures do the rest. Another thing you can do is the “no discard method” in which you just keep a certain amount of starter in the fridge and if you want to bake Saturday morning, take a small portion on Friday and feed it at a higher ratio (1:10:10 or more, or 1:5:5, this will depend on the kitchen temperature mostly). This will entail a bit of trial and error, as you see how long higher ratios take to grow in your specific conditions etc. (my kitchen during summer 1:10:10 is about a 12h cycle, for example).

Basically, bacteria keep multiplying as long as they have food, the ratios will vary depending on your schedule, temperature, flour etc… But if you want to minimize waste, the no discard method is a good approach; and since the SD will be fed a lot of flour, it’ll grow slower and have enough time to acclimate to room temperature while still growing well. I hope this helps! 🙂

This has been SO interesting to read – it all makes more sense now! Thanks so much for sharing!

Thank you so much for reading it! I’m glad it was helpful 🙂

wow.. I started out wanting to bake. loaf of rye this past Wed.been reading all week and now i want to start my starter amd make sour dough braided rye..lol..i have read it takes 7-15 days for starter to be ready to bke with.. is this true??

It is if you start building it with flour. You need to make sure the bacteria re-hydrates and eventually you have only the sourdough bacteria. It’s common for new sourdough starters to have foul smells, it’s part of the process though, and eventually they’ll have their characteristic sourdough smell.

However… if you want a slightly shorter method you can try to build a starter with fruits! I have a post about creating pasta madre for panettone, and it starts with creating a liquid starter from apple water. You can find the post here: How to create Lievito Madre (Pasta Madre) for panettone

If you follow that method you just need to stop on day 3, and from then on just feed your starter equal amounts of flour and water.

Hope this helps!!

I loved this, very thorough research and clear explanations. Looking forward to next Science Friday!

Thank you so much!! 🙂