The time has come! After several tests and experiments, I can 100% confirm that my lievito madre (or pasta madre, or LM or PM, you’ll see both in this post) is healthy and ready for the “grandi lievitati”!

This is a long post, so buckle up! Get some water, a couple of snacks, and let’s get to it!

In this post, you will find all the problems that I encountered with my pasta madre and how I fixed them one by one. You will also learn how certain factors affect the pasta madre and why from a scientific point of view.

After four months of insanity over the wellness of my lievito madre I have finally brought it back to full strength. It’s been a long journey full of troubleshooting and note-taking. I can now conclude that it wasn’t a single problem that was causing the LM to be weak, but several that I had to fix one by one.

A few pointers and clarifications

I started the LM with fermented apple water and from there I built a liquid starter (100% hydration). Then I converted it into a 35% hydration starter. You can check this post to see how I did it.

I’d like to remark that Pasta Madre is not just a stiff starter, it’s a low hydration stiff starter with very particular maintenance conditions and a very specific way to prepare it for baking. This method promotes very specific strains of bacteria and yeasts in a very specific ratio to keep a very specific pH.

Pasta Madre has an incredibly strong fermentative power that’s able to ferment dough with an incredibly high amount of sugar, butter, and egg yolk (substances that can inhibit the growth of bacteria and yeast and hinder gluten development)

Panettone, Pandoro, and Colomba di Pasquale are the holy trinity of pasta madre baking. They undergo long fermentations that due to the specific methods designed for pasta madre, the dough does not develop any acidity.

Pasta madre vs stiff starter

For example: If you’re reading this, I’m pretty sure you’re familiar with “the lievito madre must triple in 3-4h at 28C three consecutive times before it’s ready to make panettone”

If your lievito madre can do that, then it’s mature and ready to prepare the primo impasto (the first dough). However, let’s say that you prepare a stiff starter at 60% hydration. If you compare this stiff starter with pasta madre, you put both in a chamber at 28C and let them ferment, I assure you the fermentation speed will be COMPLETELY different.

Therefore, the “triple in three hours” rule for the pasta madre cannot apply to this 60% hydration stiff starter. And the triple in 12h rule for the primo impasto will not apply either because a 60% stiff starter does NOT behave the same as Pasta Madre. Keep in mind that artisan recipes and methods to make Panettone the Italian way are designed to be used with Pasta Madre.

Let’s start from the beginning

When I first started my LM I was using W380-400 Manitoba flour from Molino Caputo, but I ran out if it and I had to buy more. The new flour I received was W400 Manitoba flour from Molino Grassi.

When I changed the flour, the first thing I noticed was that the new flour needed more than 35% of water. It was impossible to incorporate all the flour. So, I started to add a little more water. Until I was using 40% of water. That extra 5% messed the whole bacteria/yeast ratio. Why? Let’s talk about “water activity”.

Water activity and what it means in food

In Food Science, water activity is a very important concept. The FDA defines water activity as “the ratio between the vapor pressure of the food itself, when in a completely undisturbed balance with the surrounding air media, and the vapor pressure of distilled water under identical conditions”.

The water activity of pure water is 1 and it’s the maximum possible value in a 0-1 range.

In essence, water activity is a way to quantify how much water there is in a particular sample, and based on that number we know which microorganisms could grow in that sample. This is particularly important for all fermentation operations, shelf-life studies, etc.

Water activity in my lievito madre

Back to my pasta madre; now you understand why that extra 5% of water I was adding created an unbalance between the Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and the yeasts in the culture. The water activity changed and it either promoted other strains of bacteria to grow or a faster proliferation among yeast strains. Or maybe even both things happened.

What was clear was that the higher water activity wasn’t promoting the best environment for the microorganisms that should be in lievito madre. In a healthier LM this wouldn’t have been such a problem, but there were other factors affecting it.

Problem #1: Alterations in the water activity of the lievito madre

Cause of the problem: impatience while incorporating flour

Solution: patience! I started to let the PM rest for a few minutes after I managed to incorporate the flour. Like a little autolyse. I went from needing 40% of water and struggle to a 35% and no problems.

Effect of flour in my lievito madre

As I mentioned, I had to change the flour I was using because the website I was buying from changed the supplier. The new flour was SO STRONG! Strong flour must be the best for panettone, right? WRONG.

Manitoba flour comes from a type of hard wheat with higher protein content. However, in order to have that high protein content, the flour has to be very refined and stripped off as much bran as possible. But this process also takes some of the nutrients of the flour away. Nutrients that the bacteria need to be able to perform their biological activities… See where I’m going?

It seemed as if my LM wasn’t getting enough nutrients every time I refreshed it, which caused a progressive loss of fermentative power. I was, unknowingly, starving my LM to the point of almost zero strength.

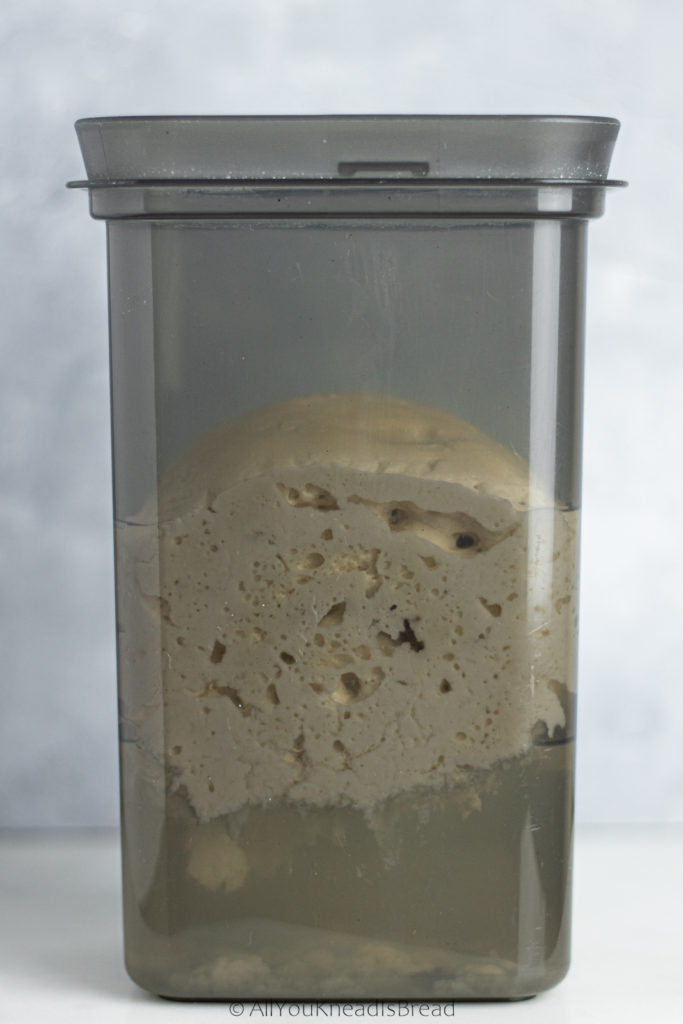

The smell told me there was some fermentation going on, probably from the yeasts, but it barely grew, it didn’t have the crumb-like inner structure, and it didn’t even float in the bath after 24h.

Problem #2: starvation of my LM

Cause of the problem: lack of nutrients in the flour.

Solution: A mix of flours with a less refined flour that would provide more nutrients.

Lack of nutrients in the flour

Talking to my friend Kel (@wonky.loaf.of.sourdough), she pointed out that maybe the flour was, indeed, too refined. And she was right! That night, when I was about to throw away the LM and start from scratch, I decided to do one last experiment. I refreshed the LM and put it in the fridge, and with the discards, I created a sibling, which I fed 80% of Manitoba flour and 20% of King Arthur bread flour.

In about 12h it was floating and showing signs of life. 12h is a long time, but previously, my LM wouldn’t float after 24h. So, this was clearly the 1st win!

Since that moment I always feed my LM a mixture of flours. I tried 15% of bread flour but it showed lower activity, and I tried also 25% of bread flour but after a feeding cycle I lost a lot of LM, it disintegrated very fast. Once I ran out of bread flour, I started to use King Arthur High Protein flour or King Arthur AP flour, whichever I had at the moment.

The second feeding went even better, in 3-4h it was floating and happy. It smelled so well, it was spongy, it was getting healthier! Or so I thought… It was better, but not 100% there. While this was definitely the major problem, there were still lots of things I wasn’t doing right.

Small changes made all the difference

I used the LM to bake a few loaves and it worked well. I tried to make sandwich bread and the dough rose well too. But when I used it to make brioche it was extremely difficult to incorporate all the butter. This is usually a sign that something is not right.

I also noticed that the loaves I made with LM had large lumps that didn’t disappear after baking. The dough wasn’t absorbing the LM and it wasn’t fermenting, because the lumps didn’t puff up while baking.

At this point I was using the 80-20 mix of flours, 35-37% of water and I was rolling the dough with my pasta maker. The temperature of the house was around 66-69F. The temperature was adequate, the flour was adequate, the hydration was adequate…

Again, Kel to the rescue! She suggested that maybe I was rolling the dough too thin and I was working the gluten too much.

The reason I was rolling the dough with the pasta roller was plain laziness! At this point I had been refreshing the PM once a day for several weeks, it became a tedious task. The pasta maker made the process much faster, but I was compromising the gluten.

Effect of gluten in my lievito madre

The temperature, flour mix, and hydration were good, and in the conditions necessary to promote proper fermentation. However, the dough structure also plays a role.

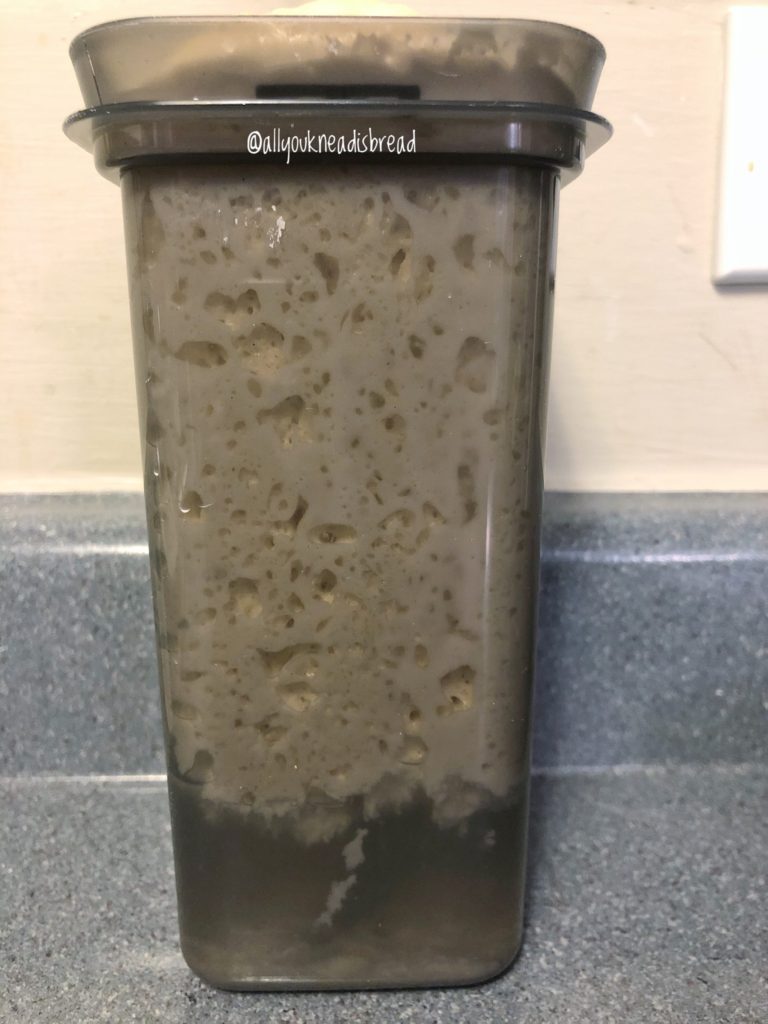

When I started to roll the dough with the pasta maker, I developed to gluten too much. To the point were 1) the dough was too thin and extremely elastic, making it easier to roll it very tight before putting it in the water bath, and 2) the gluten was so developed that after a feeding cycle, the part touching the water was degrading much faster.

I believe that by working the dough with the pasta maker and rolling it too tight, the oxygen availability in the core of the LM was low, which probably led to a proliferation of yeast and a change in the metabolic pathway of the microorganisms; which led to the development of a different aroma profile and higher production of acetic acid. It was making the dough sourer than it should.

Gluten structure vs development of aromas

A tight LM also meant that all the volatile components released during the fermentation didn’t have a place to go, the dough was so tight that they couldn’t move much and they probably were kept in the core of the LM instead of flowing into the water bath. This too increased the acidity of the pasta madre.

The part that was touching the water, disintegrated much faster. The layers were so thin that after a few hours in the water they dissolved. So, the center part was too dry and the outer part too wet.

I learned that rolling the dough too thin and too tight is detrimental to the dough in the long run. At the beginning you might not feel the difference and the smell changes so very slightly that you don’t even realize it’s becoming sourer.

Once I started to roll the dough by hand, the smell started to change, and it got much better in just 2 feeding cycles. The looser structure helped the LM develop a much better crumb-like core.

Problem #3: The dough was still showing signs of weakness and the smell wasn’t great yet

Cause of the problem: machine rolling affected the fermentation by affecting the gluten structure.

Solution: go back to hand rolling

Effect of maintenance temperature

I had spent 4 months like a doctor trying to figure out the disease of the patient. I didn’t know what was happening, so I started to rule things out. At this point I was pretty confident the LM was healthy, and the best way to test how the LM is doing is by trying to make panettone.

Everything was looking right, the hydration, the flour, the rolling method… the house temperature was a bit higher but it shouldn’t be a problem, should it? WRONG but I didn’t know it yet…

One day I woke up early, I had done the bagnetto the night before, and I started to do the 3 refreshments to prepare the LM for panettone. So that day I prepared the primo impasto and let it ferment for 12h at 28C.

At most, the primo impasto should take 14h to triple. But mine barely doubled in 15h

Obviously, my lievito madre was not ready yet. I should have known, as 4h after the last refreshment it wasn’t even floating, it hadn’t tripled in size either, but I was so eager to try to make panettone that I ignored the signs. I didn’t proceed with the secondo impasto, there was no point (I made waffles with the dough, there’s no dough that a waffle maker can’t fix!)

Effect of pH on my lievito madre

After the panettone fail, I decided to taste the LM on each refreshment (I should’ve done it earlier and more often), it was the only thing I hadn’t test yet, the flavor. And OMG! The dough did smell acidic but nothing too weird. But the taste? It was spicy, vinegary… it was super sour!

As it appears, those warmer days, once again, disrupted the equilibrium between bacteria and yeast during the maintenance refreshments. And I believe the warmer temperatures helped in the proliferation of yeasts that led to a drastic increase in the production of acetic acid and a pH unbalance.

pH is one of the factors that affect the survival conditions of the microorganisms. If the pH changes, so will the strains of microorganisms that can grow in that environment.

In need of a deep cleanse

The LM needed to be purified. I decided to do a bagnetto and then I proceeded to do the refreshment as usual. But this time I added 4% of egg yolk to buffer the acidity and help reestablish the microorganism colony. It worked wonders! (This is a technique suggested by Italian Maestros)

I only used egg once, the following days I only use flour and water and I made sure the water bath was at 4C so with the warmer temperature in my house I could keep the LM temperature at bay. The acidic taste got milder and milder until one day I tasted the LM and it was just PERFECT. It had a hint of acid, and a hint of sweetness.

The smell was HEAVENLY. It smelled alcoholic, but with a little bit of acetic acid, and something sweet. Overall it was a very very very pleasant smell. The kind of smell that you just know is right.

Problem #4: a drastic pH change

Cause of the problem: higher temperature during maintenance feeding cycles disrupted the yeast:bacteria ratio again.

Solution: purification step with egg yolk in one refreshment and cold water for the bath to compensate for the warmer temperatures.

Finally: the panettone test

I tried to make panettone again, this time pretty confident because the smell was SO GOOD that I just knew that was how it was supposed to smell (and taste!)

It was just amazing how much better the LM grew during the 3 preparatory refreshments. Even more so when I made the primo impasto. It barely had any lumps of LM in the dough, and the ones it had were very small. The dough absorbed the butter and egg yolk beautifully! (if the pH is not where it has to be, it’s difficult to for the dough to absorb fats). Even the gluten was formed differently. I could tell the pH of the LM was exactly where it had to be.

I finished the primo impasto at 9:30 pm and left it at 28C overnight. Next morning, just 11h later, it had already tripled.

I cannot express the happiness I felt when I saw it. Every time I try to make panettone, the night of the primo impasto I can’t sleep. I’m nervous it won’t rise. But that night I slept well, because I knew the LM was healthy.

It worked! Panettone on the way!

So that day I proceeded with the secondo impasto and made the panettone. And I cannot tell you how amazing the secondo impasto was. The dough was super silky. I can tell it had been my very best gluten development so far. The windowpane test was just incredible (You can see it on my highlights on my Instagram).

After 4 months of frustration, experimentation, speculation, and research. I can finally say that I brought my LM back to its healthiest life. Actually, not back, because it has never been this healthy before.

If anything, working with my pasta madre has been a humbling lesson and a reminder that this is science. Once I started to work with my pasta madre as I would with a project in the lab, things started to change, I started to see the problems and mistakes I was making. And I’ve learned so much!

Acknowledgements

If you’ve made it this far, I’d like to thank you for reading all this. And if you’re struggling with your pasta madre, I hope my experience can help you in your journey.

Also, I’d like to say thank you so much to all of you who followed this journey and gave me ideas or simply asked about my LM. Brainstorming with others is always better! And thank you to my friend Kel. Without her nerdy mind, I probably wouldn’t be here today, with a healthy pasta madre!

#missionpanettone is now stronger than ever!!!

Happy baking!!

Maria

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.

How to create Lievito Madre (Pasta Madre) for panettone

UPDATE: This post has been updated to add some modifications to the process of creating your own lievito madre or pasta madre. The new information will be in colored boxes like this paragraph.

Hello everyone!

As promised, here’s my guide to building a lievito madre or pasta madre to make panettone. I will use both names because it came to my attention that some people are using the term lievito madre to refer to liquid sourdough and it’s not the same. I want you to get familiar with both names so you know that lievito madre or pasta madre are the same thing 🙂

First of all, I want to say that all this is not my idea. I’ve been reading blogs and watching videos to have a better understanding of the whole process. Eva’s posts were full of information. I’ve been tracking down everything the Italian Pasticcieri had online and read scientific publications to understand better how bacterias work (surprisingly there’s not much research on this).

This guide is a summary of everything I’ve read and everything I’ve learned every day, and I hope it can be useful to you. It’s focused on building and training the lievito madre. The next step will be the 3 refreshments before making panettone, which I will write about once I’m more familiar with the process.

For a better understanding of how sourdough bacteria grow, I recommend you read this post first. It’ll help you understand how pasta madre works.

When I first heard about panettone, I never thought it was this incredibly challenging bread! It never even occurred to me that it was made with sourdough or how laborious the process was!

To be honest, I do have a panettone recipe here, and trust me when I tell you that I spent a lot of time trying to get the dough right, but now… I feel like I was cheating! (I still think it’s a good place to start getting familiar with very enriched dough and gluten development).

A few notes about pasta madre

First and foremost, is not just a firm sourdough starter. This stiff dough is indeed a sourdough starter, but a special one. It requires a very specific maintenance routine and it has a very specific purpose: to bake grandi lievitati products such as panettone, pandoro, colomba…

If you want to make some rustic Italian bread using sourdough, you can create a stiff starter, or use your own sourdough starter. You wouldn’t need lievito madre, because you wouldn’t need the specific characteristics of grandi lievitati products in a rustic loaf.

Grandi lievitati bakes also require very strong flour, and most likely, your regular bread flour won’t be enough. Also, I wouldn’t say that nobody uses whole wheat flour, but I believe that’s not the most common way to maintain pasta madre.

Things you need to know before you start

These are things that I’ve learned along the way and that I think everyone should know before making the decision to start this journey.

- Be aware that it’s going to take 15 days to get the lievito madre ready. There are two major parts in this process: building the stiff starter and training it.

- I encourage you to do a few experiments to see if you can find a place where you can keep a constant temperature of 30C/86F. This step is crucial in the first couple of days and also to ferment the panettone dough.

- Check your schedule and plan accordingly. Don’t start making the starter on a Saturday at 1 pm if you won’t be home at 1 pm during the week because the cycles are either of 12 or 24h.

- Gather all your ingredients before you start and make sure you have enough flour. You will need it. I bought 15lb and it’s enough to prepare the pasta madre, train it and make at least 1 batch of panettone (probably more).

- If the quality of your water is not good, buy water (you don’t need a high mineral concentration in the water). If the quality is fine, I suggest you filter the tap water.

- Get your mind in the right place. Some days you will be tired and will want to go to bed, but you’ll have to feed your pasta madre, this is very important when you’re training it. The whole point of this is to reduce the acidity. Once is matured, you can put it in the fridge and feed it once a week.

- Be patient. Use your eyes and, especially, your nose to let the dough tell you what’s happening.

The process of creating your lievito madre

| Building period | |

| Day 1 | Make apple yeast water |

| Day 2 | Create a 100% hydration sourdough |

| Day 3 | Convert into a stiff starter and start anaerobic fermentation (wrapped log) |

| Day 4 | Wait. Nothing to do |

| Day 5 | Collect the core of the log, refresh it with flour and water and start fermentation in water |

| Training Period | |

| Days 6-10 | Refreshments using same amounts of flour and starter +30-50% of the weight of flour in water |

Building the lievito madre: 5 days

The first step of the building period is to activate the wild microorganisms found on apples. In other words: create an apple yeast water.

As you know, vegetables, fruits, cereals, etc have lactic acid bacteria and yeasts that are dormant and need to be activated.

These microorganisms, in general, proliferate better when their environment is moist. In science, we refer to this as “water activity”. This number ranges between 0 and 1 (pure water being 1), so the higher the water activity, the easier it will be for the microorganisms to wake up and grow.

Temperature is also crucial. Fermentation can occur at different temperatures, but not all microorganisms are activated at the same temperature. For panettone purposes, we should make sure our culture is at 28-30C (82-86F) so we promote the fermentation of specific strains of lactic acid bacteria.

A typical sourdough culture can have dozens of different strains of bacteria and many different types of yeast. So we can select which ones we prefer by controlling the temperature, moisture content, pH…

Day 1: Start the apple yeast water

You will need:

- 1 or 2 pesticide-free and untreated apples (I bought organic and they worked great, they shouldn’t have wax or anything, the more natural the better. If you can go to an orchard even better!)

- A glass container with a lid

- A grater

- Water at 30C/86F ( I used tap water filtered with my Brita)

- A scale

- A knife

- A thermometer

- A warm place where you can maintain a temperature between 28-30C/82-86F (my oven with the light on is enough, if it’s too cold and the temperature drops in the evening I put a glass with hot water on the other corner of the oven before I go to bed or when I wake up)

- Cut the apples in 4 and remove the core. You don’t need to clean the apples because if you do, you’ll probably wash out lots of nice microorganism. If there’s dirt on the stem area, just cut that part out.

- Grate the apples and keep the peels

- Weight 200g of grated apples and peels an place them in the glass container

- Weight 200g of water at 30C/86F

- Add the water to the glass container and close it tightly. You can shake it a little bit if you want

- Place the container in your oven or fermenter and wait for 24h

That’s it for now!

Day 2: create a sourdough starter with the apple yeast water

After 24h you might see small bubbles in your container, it can make a fizzy noise when you open it, it can smell like cider or maybe you can’t tell if something happened in there. That’s why this step is important. If after 24h, your starter doesn’t show activity, start with the apples again because something went wrong.

You will need:

- Fermented apple mixture from day 1

- A strainer

- A tall and transparent container*

- A spatula or a spoon

- 200g of Manitoba flour

- A scale

- Sharpie or rubber band to mark the container

Today is an easy day, enjoy it, because things get more complicated!

- Strain the apple mixture from the day before and collect the liquid. In my case, I didn’t see small bubbles, but it did smell like cider.

- In a medium bowl weigh 200 g of Manitoba flour and add 200 g of the fermented apple water. With a spatula mix well until you don’t see dry flour particles. It should look like a regular 100% hydration starter.

- Carefully transfer the starter to the tall container. And let it ferment at 30C for 24h. I put it in the oven with the light on. After 24h the starter will raise and collapse. At the very least it should double in size. That’s why it’s important to not leave dough stuck on the container wall because while the starter rises and collapses it’ll leave a mark on it, so you’ll be able to tell how far it rose. If there was anything there before, you might get confused.

NOTES:

You don’t have to put a lid on the container, you just need to place a napkin on top it there is any risk of something falling inside.

If you have it in the oven, try not to open the door all the time. That way you avoid streams of colder air coming inside and changing the temperature. The more constant the temperature the better. I checked my oven before going to bed and in the morning if the temperature changed too much overnight or I felt the house very cold.

Make sure the container you use for this is tall enough that can hold the dough even if it quadruples in size. Also, just in case some starter overflows, put a plate or a tray underneath.

*my container is a coffee canister that I bought in Walmart for less than $2. It’s 10x9x20 cm (4×3.6×8 in)

Day 3: Convert the starter into a stiff starter and do an anaerobic fermentation

Today is when you should start seeing activity in the sourdough. After 24h at 30C, your sourdough should’ve grown and collapsed. There should be some debris on the walls of your container that indicates how high the starter rose. It should’ve, at the very least, doubled in size. If it didn’t, at least, double, I’d start again. There aren’t enough bacteria or the ones that are in the culture, are not strong enough.

You must always keep in mind that making panettone is a difficult task and fermenting all that dough full of sugar, butter and egg is difficult too. So, we need to make sure that the bacteria we select and will train is the strongest.

The starter should be very runny, the same as a 100% hydration starter that has reached the peak and collapsed. It should have small bubbles on the surface and a pungent aroma. Don’t freak out if it smells like something rotten, so far, it’s normal. The bacterial colonies are fighting against each other, everything we do is to promote the survival of the ones we want.

The second time I built my LM I didn’t wait until it completely collapsed (24h), instead, I decided to proceed with the next step after 12h. This way most of the bacteria were still in the stationary phase, which means that I collected more live bacteria. Ultimately, my PM was more active than the previous one.

You will need

- 200 g of yesterday’s starter

- 200 g of flour (more if needed to achieve desired consistency)

- A rolling pin

- A scale

- A Ziplock bag

- 2 cotton cloths

- 1 meter/1 yard of some strong rope or string

- Collect 200g of the starter and add 200 g of flour.

- With your hands mix everything well. The dough should be dry and relatively hard, it shouldn’t stick to the counter but should be soft enough to work with a rolling pin. It is OK if you need to let it rest a few times to relax the gluten.

- Once you’ve incorporated the flour, with a rolling pin start working the dough until it gets a little bit more elastic. It doesn’t have to be extremely soft and smooth, but it shouldn’t have lots dry flour or chunks of dry flour either.

- Shape the dough into a rectangle-ish that’s about 20cm long and 15cm wide and roll it into a log. Place it into the ziplock bag and wrap it well. Wrap the packet with a cotton cloth and then with another cotton cloth and tie it with the rope or strings you have. It doesn’t need to be too tight, just enough to keep the cloths in place.

- Put the dough in an empty pot and put the pot inside of your oven (this is precaution, it can explode due to the built-in pressure). You don’t need to leave the light on. Just make sure that nobody turns the oven on and burn your pasta madre.

- Let it ferment for 48h. As time goes by the log gets harder and harder. That’s a good sign. It means that it is fermenting and as a result, the pressure is increasing.

Day 4: No need to do anything

Day 5: Collect the fermented stiff starter and begin the fermentation in water

After 48h the log might not feel as tight as after 24 or it might still feel a bit tight. Anyhow, today we’re going to unwrap the whole packet. Be careful because it can explode. Most likely, you’ll see how, due to the pressure built inside, the dough tore apart the plastic bag and some of it came out and it’s dry and stuck on the cloth. Don’t worry, it’s absolutely normal.

You will need:

- A knife

- A scale

- 200 g of stiff sourdough

- 200 g of flour

- 60-100 g of water at 30C/86F

- Mixing bowl

- Rolling pin

- A tall and transparent container

- Water for the bath

- Unwrap the log carefully

- With a knife cut the bag and open the log lengthwise. You should see small alveoli. The dough should have a dark color (from the apple water) and it should smell better, more of a fermentation smell than in the previous step.

- With a clean spoon, collect the inside part of the log (the “cuore” as Italians say). The strongest bacterial colony is in the core of the log. The bacteria undergo a very rough 48h where an anaerobic fermentation takes place and only the strong survive, and those are the ones we want.

- Collect 200g of dough or as many as you can.

- In a bowl add 200g of dough, 200g of flour and 30-50% of the weight of flour in water at 30C/86F. That is 60-100 g. Start by adding 30% and move up if needed. The dough should be dry and hard, it shouldn’t stick to the counter but should be soft enough to work with a rolling pin.

- Roll the dough into a rectangle, fold it in 2 or 3 and roll it again. The procedure is very similar to working with laminated dough.The dough should get smoother and smoother. It shouldn’t have pieces of dry flour in the middle.

- Roll the dough into a long rectangle that is slightly narrower than your container and about 1cm/0.5 in thick.

- Fold the rectangle into 3 or 4, put it inside of the plastic container and fill it with water just to cover the dough.

NOTES:

If your kitchen is:

- Cold-Very cold: you can use room temperature water for the bath

- Not too cold, not too warm (around 20-23C, 69-73F): you can use room temperature water and check how it evolves, you might be able to do refreshments every 12h or every 24.

- Warm-very warm: use cold water. Keep a bottle of water in the fridge, or cool it with ice cubes and when it’s cold enough add it to the container.

Pay attention to how the dough behaves. Warmer temperatures will accelerate the fermentation process and colder will slow it down. Avoiding over fermentation is crucial.

In my case, my kitchen was not too warm and not too cold, but since I’m not home all day, I didn’t want to risk the dough to over ferment and lose a lot of it, so I started using cold water. The dough didn’t show much sign of fermentation in the first 12h. After 16h it was floating and after 24 it had clear signs of fermentation (alveoli), the layers weren’t visible anymore and it had developed a dry skin on top.

Something I realized was that this sourdough starter likes routines, so try to always do the same thing and keep it at the same temperature. During this process, there was a night when the temperature dropped a lot and the pasta madre didn’t rise as usual. In my experience, consistency is key!

The reason the container and the dough should be almost the same width is that when the dough starts fermenting and the layers get thicker, the container will retain the dough and prevent it from expanding to the sides. Therefore, the dough doesn’t have a choice but to grow upwards.

Training your pasta madre: 10 days

Days 6-15: refresh the lievito madre every 12 or 24h

According to the Italian regulations for Artisanal Panettone, the lievito madre has to be trained for at least 7 days. In our case, it’ll be trained for 10 days.

From now on you need discipline because you must feed your LM at the very least every 24h. Whether you’re tired or sleepy. Therefore, you need to think well about which schedule works for you best.

For example, I leave my house around 8:45 am, and come back home around 8 pm, that’s my window. I started the process at 8:30 pm and then I was doing the refreshments at 8:30 pm every 24h. I chose this time because not only is it when I’m home, but it’s also a time that works for me on the weekends. Because your pasta madre doesn’t take weekends off!

I’m saying this because if you start working very early, you might do refreshments at 5 or 6 am, but… will you wake up that early on a weekend? If you will, then it’s fine! I know I wouldn’t, I’d probably turn my alarm off and regret it later.

You will need:

- A knife

- A scale

- 200 g of stiff sourdough

- 200 g of flour

- 60-100 g of water at 30C/86F

- Mixing bowl

- Rolling pin

- Tall and transparent container

- Water for the bath

- A large bowl to discard the water or the kitchen sink

I changed my container to a shorter but wider one after day 6 or 7. It allowed me to control and shape the dough better.

The procedure is similar to day 5.

After 24h, the lievito madre should’ve risen to the top of the container and probably developed a dry skin. In the bottom, you will see some flour. Your pasta madre will be very soft and slimy on the outer parts. What we need is the core of the dough.

- Remove the dry skin that developed on top. It might not be completely dry, but even so, remove it. It’s the part that has been exposed to dust and particles falling on top of it.

- Hold the container with one hand and with the other try to separate the dough from the walls of the container so the water to come out but you can hold the dough, and remove the water.

- Squeeze the dough to drain water out of it and massage it so the slimy mushy part falls out and you only keep the dough that was not degraded.

- In another bowl weigh 200g of Manitoba flour, add 200 g of the drained pasta madre and add 60-100 g of water at 30C/86F

- Knead everything and incorporate all the flour. If you need to let the dough rest, do so.

- Roll and shape the dough the same way you did the day before

- Place the dough in the container and add water to cover it.

Repeat this every day for the next 10 days paying attention to how the dough smells, how the alveoli look after the fermentation cycle etc. Also, smell everything. The dough, the water you discard… Your nose will let you know how the lievito madre is doing more than your eyes will.

Things you need to know

- You need to keep everything extremely clean to reduce the chance of cross-contamination.

- Keep in mind that you’re going to use a lot of flour just to build your starter. If you’re a pro at this, probably you can use smaller amounts of flour and LM because you can tell how the dough is doing just by looking at it. But if you’re like me, in the learning process, you might want to keep relatively large amounts of flour for each refreshment until you learn to feel the dough and see if it needs more or less water, 24 or 12h refreshment cycles, etc. I learned this method this way and larger amounts are easier to deal with and to avoid over-degradation of the dough. This is especially handy when you’re not home all day. I see this as an investment, from now on I’ll take care of my lievito madre and, hopefully, I won’t have to do it again!

- Your hand will suffer, keep your moisturizing lotion close by! After a few days I noticed my hands were getting very dry. I guess it’s normal, you’ll be washing your hands all the time, and let me tell you… this dough is difficult to get rid of! Warm water is your best friend here. Also, you’re going to be working every day with a slightly acidic dough. So yeah, keep the lotion close by.

- If you can find/afford 2 containers with the same dimension, get them. It’ll make the process a bit faster because you don’t have to stop to wash it to put the dough back in.

That is all for now!

This is all for now. If you have any questions you can contact me through email, DM on Instagram, or send me a message on Facebook and I’ll try my best to help you!

Let’s start a movement for homemade artisanal panettone! Tag your pics with the hashtag #missionpanettone so we can all see how everyone’s lievito madre is doing.

You can find me on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest, and you can also subscribe to my Youtube channel.

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.

I hope you all have a wonderful weekend and if you are celebrating Thanksgiving… Happy Thanksgiving!

Maria.