The time has come! After several tests and experiments, I can 100% confirm that my lievito madre (or pasta madre, or LM or PM, you’ll see both in this post) is healthy and ready for the “grandi lievitati”!

This is a long post, so buckle up! Get some water, a couple of snacks, and let’s get to it!

In this post, you will find all the problems that I encountered with my pasta madre and how I fixed them one by one. You will also learn how certain factors affect the pasta madre and why from a scientific point of view.

After four months of insanity over the wellness of my lievito madre I have finally brought it back to full strength. It’s been a long journey full of troubleshooting and note-taking. I can now conclude that it wasn’t a single problem that was causing the LM to be weak, but several that I had to fix one by one.

A few pointers and clarifications

I started the LM with fermented apple water and from there I built a liquid starter (100% hydration). Then I converted it into a 35% hydration starter. You can check this post to see how I did it.

I’d like to remark that Pasta Madre is not just a stiff starter, it’s a low hydration stiff starter with very particular maintenance conditions and a very specific way to prepare it for baking. This method promotes very specific strains of bacteria and yeasts in a very specific ratio to keep a very specific pH.

Pasta Madre has an incredibly strong fermentative power that’s able to ferment dough with an incredibly high amount of sugar, butter, and egg yolk (substances that can inhibit the growth of bacteria and yeast and hinder gluten development)

Panettone, Pandoro, and Colomba di Pasquale are the holy trinity of pasta madre baking. They undergo long fermentations that due to the specific methods designed for pasta madre, the dough does not develop any acidity.

Pasta madre vs stiff starter

For example: If you’re reading this, I’m pretty sure you’re familiar with “the lievito madre must triple in 3-4h at 28C three consecutive times before it’s ready to make panettone”

If your lievito madre can do that, then it’s mature and ready to prepare the primo impasto (the first dough). However, let’s say that you prepare a stiff starter at 60% hydration. If you compare this stiff starter with pasta madre, you put both in a chamber at 28C and let them ferment, I assure you the fermentation speed will be COMPLETELY different.

Therefore, the “triple in three hours” rule for the pasta madre cannot apply to this 60% hydration stiff starter. And the triple in 12h rule for the primo impasto will not apply either because a 60% stiff starter does NOT behave the same as Pasta Madre. Keep in mind that artisan recipes and methods to make Panettone the Italian way are designed to be used with Pasta Madre.

Let’s start from the beginning

When I first started my LM I was using W380-400 Manitoba flour from Molino Caputo, but I ran out if it and I had to buy more. The new flour I received was W400 Manitoba flour from Molino Grassi.

When I changed the flour, the first thing I noticed was that the new flour needed more than 35% of water. It was impossible to incorporate all the flour. So, I started to add a little more water. Until I was using 40% of water. That extra 5% messed the whole bacteria/yeast ratio. Why? Let’s talk about “water activity”.

Water activity and what it means in food

In Food Science, water activity is a very important concept. The FDA defines water activity as “the ratio between the vapor pressure of the food itself, when in a completely undisturbed balance with the surrounding air media, and the vapor pressure of distilled water under identical conditions”.

The water activity of pure water is 1 and it’s the maximum possible value in a 0-1 range.

In essence, water activity is a way to quantify how much water there is in a particular sample, and based on that number we know which microorganisms could grow in that sample. This is particularly important for all fermentation operations, shelf-life studies, etc.

Water activity in my lievito madre

Back to my pasta madre; now you understand why that extra 5% of water I was adding created an unbalance between the Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and the yeasts in the culture. The water activity changed and it either promoted other strains of bacteria to grow or a faster proliferation among yeast strains. Or maybe even both things happened.

What was clear was that the higher water activity wasn’t promoting the best environment for the microorganisms that should be in lievito madre. In a healthier LM this wouldn’t have been such a problem, but there were other factors affecting it.

Problem #1: Alterations in the water activity of the lievito madre

Cause of the problem: impatience while incorporating flour

Solution: patience! I started to let the PM rest for a few minutes after I managed to incorporate the flour. Like a little autolyse. I went from needing 40% of water and struggle to a 35% and no problems.

Effect of flour in my lievito madre

As I mentioned, I had to change the flour I was using because the website I was buying from changed the supplier. The new flour was SO STRONG! Strong flour must be the best for panettone, right? WRONG.

Manitoba flour comes from a type of hard wheat with higher protein content. However, in order to have that high protein content, the flour has to be very refined and stripped off as much bran as possible. But this process also takes some of the nutrients of the flour away. Nutrients that the bacteria need to be able to perform their biological activities… See where I’m going?

It seemed as if my LM wasn’t getting enough nutrients every time I refreshed it, which caused a progressive loss of fermentative power. I was, unknowingly, starving my LM to the point of almost zero strength.

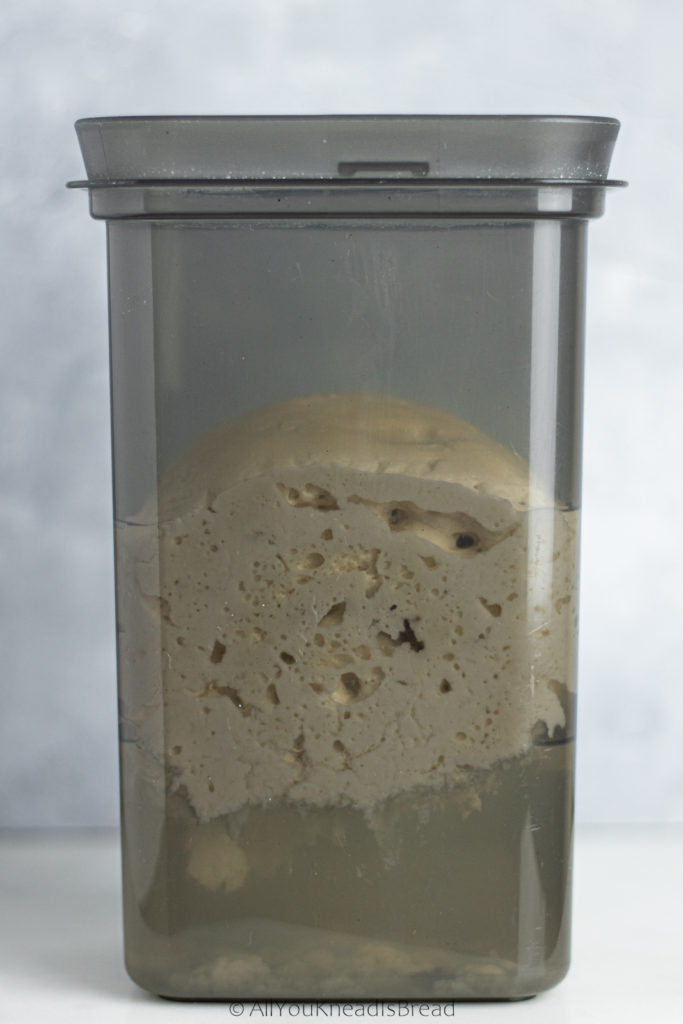

The smell told me there was some fermentation going on, probably from the yeasts, but it barely grew, it didn’t have the crumb-like inner structure, and it didn’t even float in the bath after 24h.

Problem #2: starvation of my LM

Cause of the problem: lack of nutrients in the flour.

Solution: A mix of flours with a less refined flour that would provide more nutrients.

Lack of nutrients in the flour

Talking to my friend Kel (@wonky.loaf.of.sourdough), she pointed out that maybe the flour was, indeed, too refined. And she was right! That night, when I was about to throw away the LM and start from scratch, I decided to do one last experiment. I refreshed the LM and put it in the fridge, and with the discards, I created a sibling, which I fed 80% of Manitoba flour and 20% of King Arthur bread flour.

In about 12h it was floating and showing signs of life. 12h is a long time, but previously, my LM wouldn’t float after 24h. So, this was clearly the 1st win!

Since that moment I always feed my LM a mixture of flours. I tried 15% of bread flour but it showed lower activity, and I tried also 25% of bread flour but after a feeding cycle I lost a lot of LM, it disintegrated very fast. Once I ran out of bread flour, I started to use King Arthur High Protein flour or King Arthur AP flour, whichever I had at the moment.

The second feeding went even better, in 3-4h it was floating and happy. It smelled so well, it was spongy, it was getting healthier! Or so I thought… It was better, but not 100% there. While this was definitely the major problem, there were still lots of things I wasn’t doing right.

Small changes made all the difference

I used the LM to bake a few loaves and it worked well. I tried to make sandwich bread and the dough rose well too. But when I used it to make brioche it was extremely difficult to incorporate all the butter. This is usually a sign that something is not right.

I also noticed that the loaves I made with LM had large lumps that didn’t disappear after baking. The dough wasn’t absorbing the LM and it wasn’t fermenting, because the lumps didn’t puff up while baking.

At this point I was using the 80-20 mix of flours, 35-37% of water and I was rolling the dough with my pasta maker. The temperature of the house was around 66-69F. The temperature was adequate, the flour was adequate, the hydration was adequate…

Again, Kel to the rescue! She suggested that maybe I was rolling the dough too thin and I was working the gluten too much.

The reason I was rolling the dough with the pasta roller was plain laziness! At this point I had been refreshing the PM once a day for several weeks, it became a tedious task. The pasta maker made the process much faster, but I was compromising the gluten.

Effect of gluten in my lievito madre

The temperature, flour mix, and hydration were good, and in the conditions necessary to promote proper fermentation. However, the dough structure also plays a role.

When I started to roll the dough with the pasta maker, I developed to gluten too much. To the point were 1) the dough was too thin and extremely elastic, making it easier to roll it very tight before putting it in the water bath, and 2) the gluten was so developed that after a feeding cycle, the part touching the water was degrading much faster.

I believe that by working the dough with the pasta maker and rolling it too tight, the oxygen availability in the core of the LM was low, which probably led to a proliferation of yeast and a change in the metabolic pathway of the microorganisms; which led to the development of a different aroma profile and higher production of acetic acid. It was making the dough sourer than it should.

Gluten structure vs development of aromas

A tight LM also meant that all the volatile components released during the fermentation didn’t have a place to go, the dough was so tight that they couldn’t move much and they probably were kept in the core of the LM instead of flowing into the water bath. This too increased the acidity of the pasta madre.

The part that was touching the water, disintegrated much faster. The layers were so thin that after a few hours in the water they dissolved. So, the center part was too dry and the outer part too wet.

I learned that rolling the dough too thin and too tight is detrimental to the dough in the long run. At the beginning you might not feel the difference and the smell changes so very slightly that you don’t even realize it’s becoming sourer.

Once I started to roll the dough by hand, the smell started to change, and it got much better in just 2 feeding cycles. The looser structure helped the LM develop a much better crumb-like core.

Problem #3: The dough was still showing signs of weakness and the smell wasn’t great yet

Cause of the problem: machine rolling affected the fermentation by affecting the gluten structure.

Solution: go back to hand rolling

Effect of maintenance temperature

I had spent 4 months like a doctor trying to figure out the disease of the patient. I didn’t know what was happening, so I started to rule things out. At this point I was pretty confident the LM was healthy, and the best way to test how the LM is doing is by trying to make panettone.

Everything was looking right, the hydration, the flour, the rolling method… the house temperature was a bit higher but it shouldn’t be a problem, should it? WRONG but I didn’t know it yet…

One day I woke up early, I had done the bagnetto the night before, and I started to do the 3 refreshments to prepare the LM for panettone. So that day I prepared the primo impasto and let it ferment for 12h at 28C.

At most, the primo impasto should take 14h to triple. But mine barely doubled in 15h

Obviously, my lievito madre was not ready yet. I should have known, as 4h after the last refreshment it wasn’t even floating, it hadn’t tripled in size either, but I was so eager to try to make panettone that I ignored the signs. I didn’t proceed with the secondo impasto, there was no point (I made waffles with the dough, there’s no dough that a waffle maker can’t fix!)

Effect of pH on my lievito madre

After the panettone fail, I decided to taste the LM on each refreshment (I should’ve done it earlier and more often), it was the only thing I hadn’t test yet, the flavor. And OMG! The dough did smell acidic but nothing too weird. But the taste? It was spicy, vinegary… it was super sour!

As it appears, those warmer days, once again, disrupted the equilibrium between bacteria and yeast during the maintenance refreshments. And I believe the warmer temperatures helped in the proliferation of yeasts that led to a drastic increase in the production of acetic acid and a pH unbalance.

pH is one of the factors that affect the survival conditions of the microorganisms. If the pH changes, so will the strains of microorganisms that can grow in that environment.

In need of a deep cleanse

The LM needed to be purified. I decided to do a bagnetto and then I proceeded to do the refreshment as usual. But this time I added 4% of egg yolk to buffer the acidity and help reestablish the microorganism colony. It worked wonders! (This is a technique suggested by Italian Maestros)

I only used egg once, the following days I only use flour and water and I made sure the water bath was at 4C so with the warmer temperature in my house I could keep the LM temperature at bay. The acidic taste got milder and milder until one day I tasted the LM and it was just PERFECT. It had a hint of acid, and a hint of sweetness.

The smell was HEAVENLY. It smelled alcoholic, but with a little bit of acetic acid, and something sweet. Overall it was a very very very pleasant smell. The kind of smell that you just know is right.

Problem #4: a drastic pH change

Cause of the problem: higher temperature during maintenance feeding cycles disrupted the yeast:bacteria ratio again.

Solution: purification step with egg yolk in one refreshment and cold water for the bath to compensate for the warmer temperatures.

Finally: the panettone test

I tried to make panettone again, this time pretty confident because the smell was SO GOOD that I just knew that was how it was supposed to smell (and taste!)

It was just amazing how much better the LM grew during the 3 preparatory refreshments. Even more so when I made the primo impasto. It barely had any lumps of LM in the dough, and the ones it had were very small. The dough absorbed the butter and egg yolk beautifully! (if the pH is not where it has to be, it’s difficult to for the dough to absorb fats). Even the gluten was formed differently. I could tell the pH of the LM was exactly where it had to be.

I finished the primo impasto at 9:30 pm and left it at 28C overnight. Next morning, just 11h later, it had already tripled.

I cannot express the happiness I felt when I saw it. Every time I try to make panettone, the night of the primo impasto I can’t sleep. I’m nervous it won’t rise. But that night I slept well, because I knew the LM was healthy.

It worked! Panettone on the way!

So that day I proceeded with the secondo impasto and made the panettone. And I cannot tell you how amazing the secondo impasto was. The dough was super silky. I can tell it had been my very best gluten development so far. The windowpane test was just incredible (You can see it on my highlights on my Instagram).

After 4 months of frustration, experimentation, speculation, and research. I can finally say that I brought my LM back to its healthiest life. Actually, not back, because it has never been this healthy before.

If anything, working with my pasta madre has been a humbling lesson and a reminder that this is science. Once I started to work with my pasta madre as I would with a project in the lab, things started to change, I started to see the problems and mistakes I was making. And I’ve learned so much!

Acknowledgements

If you’ve made it this far, I’d like to thank you for reading all this. And if you’re struggling with your pasta madre, I hope my experience can help you in your journey.

Also, I’d like to say thank you so much to all of you who followed this journey and gave me ideas or simply asked about my LM. Brainstorming with others is always better! And thank you to my friend Kel. Without her nerdy mind, I probably wouldn’t be here today, with a healthy pasta madre!

#missionpanettone is now stronger than ever!!!

Happy baking!!

Maria

This post contains affiliate links and any sales made through such links will reward me a small commission – at no extra cost for you – that allows me to keep running this blog.